Note: The documents cited in this section are available in the Dartmouth Library's digital collection Enslavement Documents from the Wheelock Collection.

The first mention of an enslaved person in Eleazar Wheelock's household appears in 1735. In a letter from November of that year, Wheelock refers to a girl, noting that she is very ill and likely to die. Like that of so many of the people enslaved by Wheelock, her fate is unknown, as are the circumstances under which she came to be enslaved, or came to be enslaved by Wheelock.

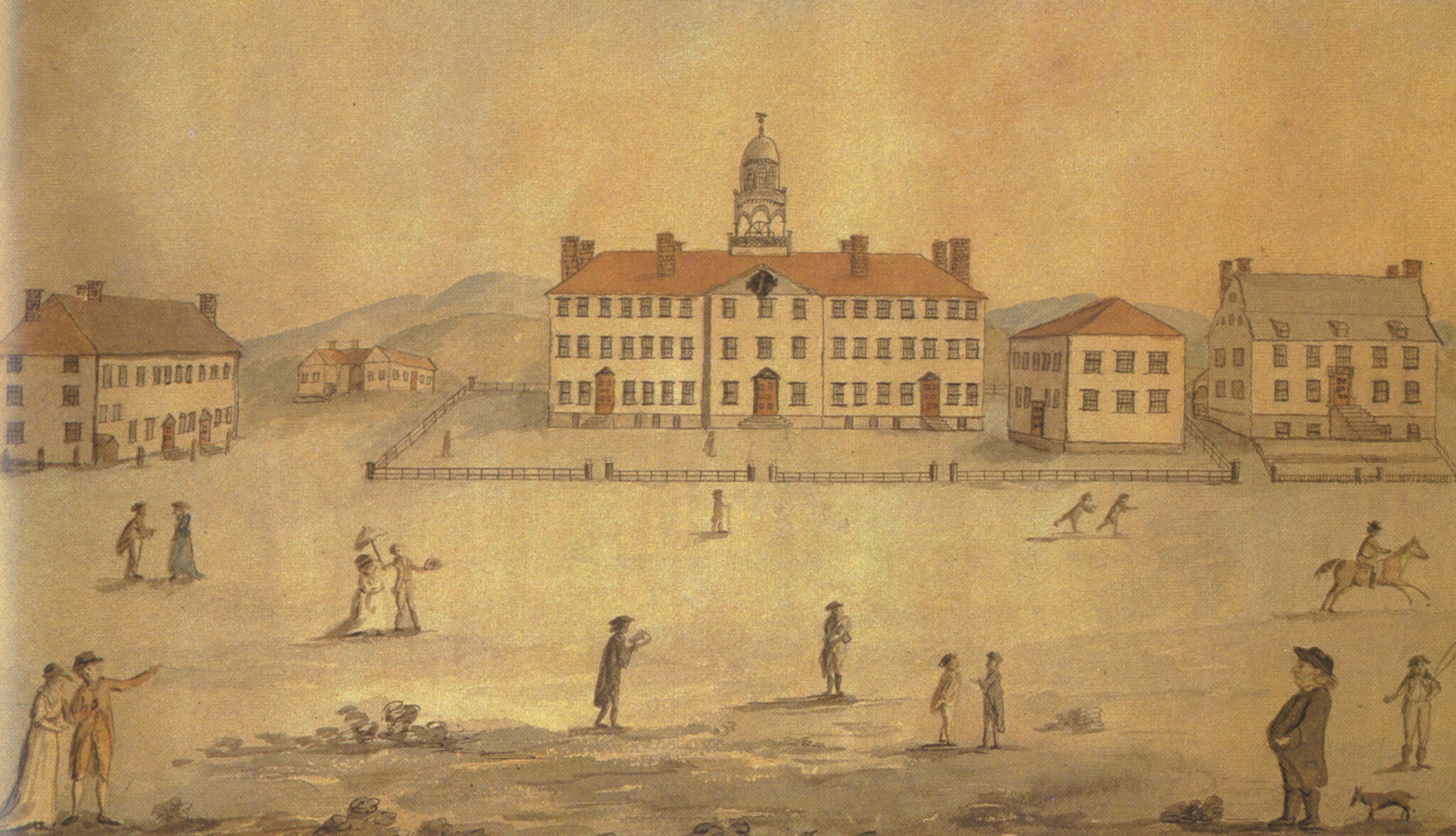

Because enslaved people were considered worldly goods, testaments to their existence are most often found in financial documents such as account books and deeds of sale. Between 1743 and 1769, there are references in such papers to the purchase of eight enslaved people, six men and two women. Nine additional enslaved people appear in other documents, including letters, warrants, accounts, and a will. In some instances, however, the records are not entirely clear—it is uncertain though likely, for example, that the 1743 bill of sale for a man named Fortune, and account book entries for someone name Fortunatus, refer to the same individual. In all, the extant record accounts for 17 individuals enslaved by Eleazar Wheelock, though it is likely he enslaved more people than these documents reveal.

For instance, a 1761 deed of sale attests to Wheelock’s buying back of a man named Sippy from two men to whom he had sold Sippy a year before. This means that Wheelock must have purchased Sippy prior to 1760, but there is no other record of Sippy’s existence, either before or after this document was written. Likewise, enslaved men named Billy and Elijah appear only in Wheelock’s account book and nowhere else in his surviving papers. In other words, it is entirely possible that Wheelock enslaved other individuals without any documentation of their existence.

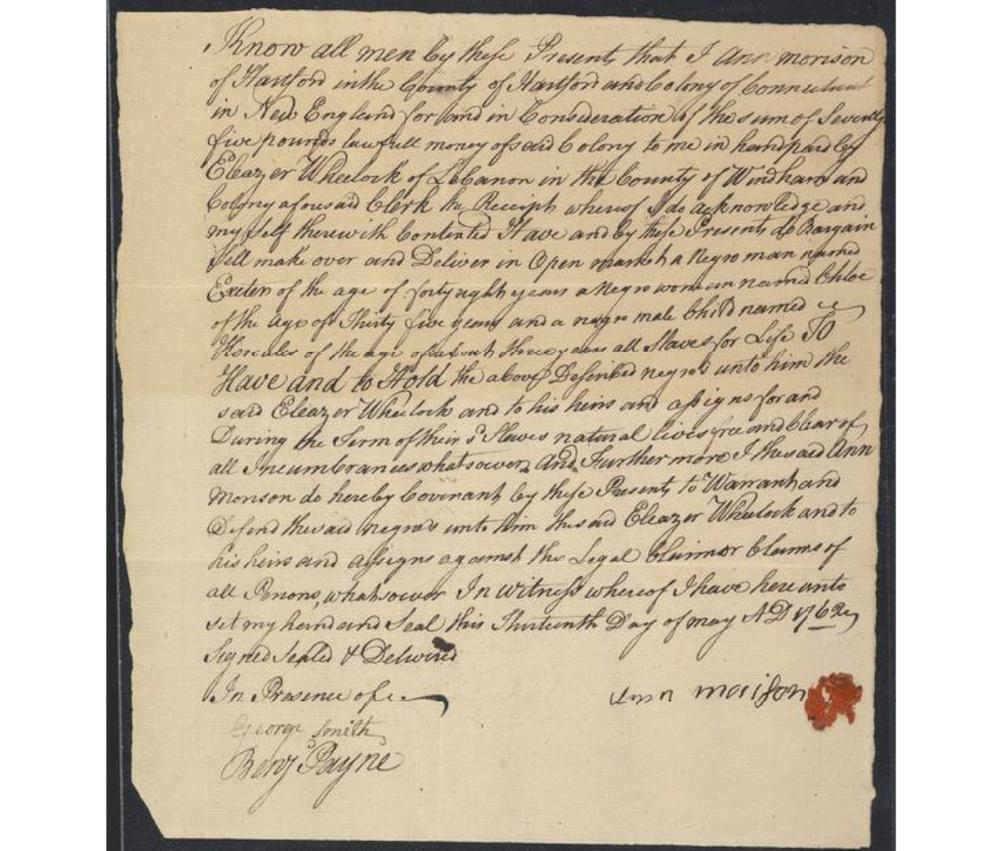

Among other surviving deeds of sale is one for the purchase of Fortune, in 1743, and a man named Ishmael, in 1757. In 1760, the purchase of a man named Brister is documented; and in 1762, Wheelock purchased a family consisting of a man named Exeter, a woman named Chloe, and a boy named Hercules. Chloe bore a daughter shortly afterwards. Finally, in 1769, the year that Dartmouth College was founded, Wheelock purchased a woman named Dinah.

In 1770, a woman named Peggy appears in a letter, but she is never referred to by name again, nor does she appear prior to this mention. It is uncertain but likely that she is the daughter born to Chloe. A man named Caesar is mentioned three times: once in a 1773 warrant issued by Wheelock in his role as justice of the peace, in a corresponding bond (similar to a bail bond) that same year, and in a letter detailing his status. A woman named Hagar and a man named Nando, who were either jointly owned by Wheelock and two other men, or Wheelock had some financial interest in, also appear in Wheelock’s correspondence beginning in 1771.

Finally, a woman named Selinda, a girl named Ama, and an infant all appear only in Wheelock’s will. Also named in the will is a young man named Achelous, who appears to be the boy named Hercules, purchased in 1762 along with his parents.

Anne Morrison to Eleazar Wheelock, bill of sale for Exeter, Cloe, and Hercules, for the sum of £75. 1762 May 13. Hartford, CT

Bill, or Billy, was enslaved by Eleazar Wheelock and put to work at a property in Connecticut

Dinah, an enslaved person, was sold to Eleazar Wheelock in 1769 by his son-in-law, Alexander Phelps

Hercules Lenson was enslaved by Eleazar Wheelock at the age of three and later gained his freedom