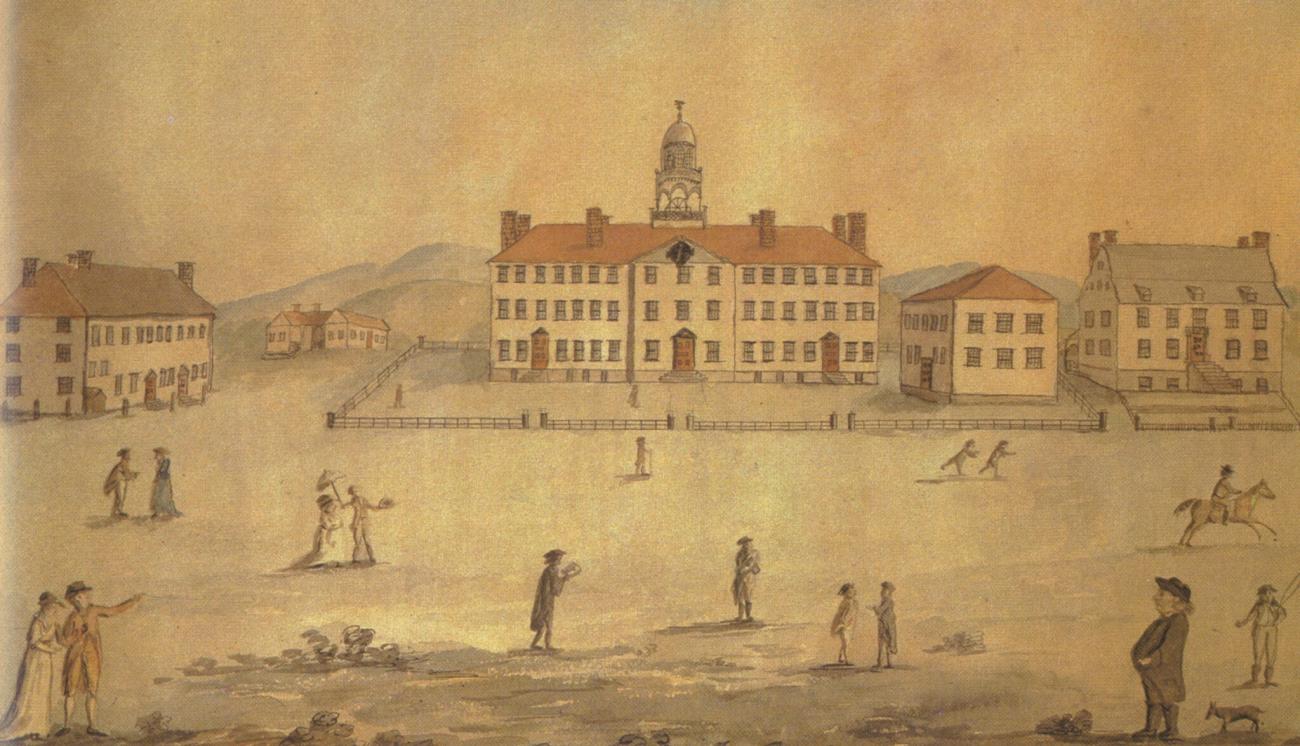

Brister, an enslaved person, was purchased by Eleazar Wheelock in 1760

BIOGRAPHY

The purchase by Eleazar Wheelock of a man named Brister is detailed in a bill of sale dated April 26, 1760. Brister is described in the document as 21 years old, “of a healthy and sound constitution,” and “free from any distemper or disorder of body or mind that may prejudice his usefulness in the capacity of a slave.”

It would appear that Brister was seen by his enslaver as capable and trustworthy—in a letter from Wheelock to his son John, dated August 24, 1769, Wheelock mentions that on a trip to Albany that also includes his daughter, Molly, he is taking Brister to “wait on me.” Four years later, however, Brister was implicated in an incident involving Mary Sleeper, one of Wheelock’s white, possibly indentured, servants. In a warrant dated February 6, 1773, an enslaved person named Caesar was charged with defaming Mary’s character by declaring that Brister and another enslaved person named Archelaus (also known as Hercules) had had “carnal knowledge” of Sleeper, and that she “was fond of it.” Caesar was arrested and charged in the case, then ordered to pay £10 in damages. If Brister was also punished, no record of it exists.

Brister remained enslaved by Wheelock throughout the latter’s life. In a will dated April 2, 1779—22 days before Wheelock’s death—Brister is named as Wheelock’s “servant man,” and granted his freedom along with 50-100 acres of land, though only on the condition that Brister marries and finds a way to support his family. He was otherwise bequeathed to Wheelock’s son, John. In an attempt to find a wife, Brister wrote to Jabez Bingham in the fall of 1779 to see if he would grant Selinda her freedom so that they could marry. Selinda appears to have been given or sold to Bingham by John Wheelock. On October 26 of that year she responded to Brister in a letter, likely written for her, that she would be happy to marry him and gain her freedom.1 What happened to this arrangement is unclear since Brister and Selinda do not appear to have gotten married. Brister did eventually manage to find a wife, marry, and have a family. He is listed as having died in 1805 in a local record that also mentions a wife named Lavinia, and two children. Brister would have been in his mid-to-late 60s at the time of his death.

The name Brister is likely derived from Bristol, following a common convention of naming enslaved persons after places in Britain.

Notes

1. Selinda Welch to Brister Wheelock, October 26, 1779, Mss 779576, Rauner Special Collections Library, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH.