Indigenous labor was an integral factor in the economic growth of New England, while Indigenous expertise about the natural environment was indispensable not just for Europeans’ physical survival, but for establishing early trade relationships, and undertaking explorations of frontiers.1 Even after the enslavement of Indigenous peoples was technically outlawed, indenturement and other forms of slavery was maintained as a way to lower the costs of housekeeping and land maintenance, and to provide colonial New Englanders with economic and social capital. As the social networks, affiliations, and conflicts of Indians were manipulated to enslave able-bodied workers, Indian servitude became heavily normalized in New England.2

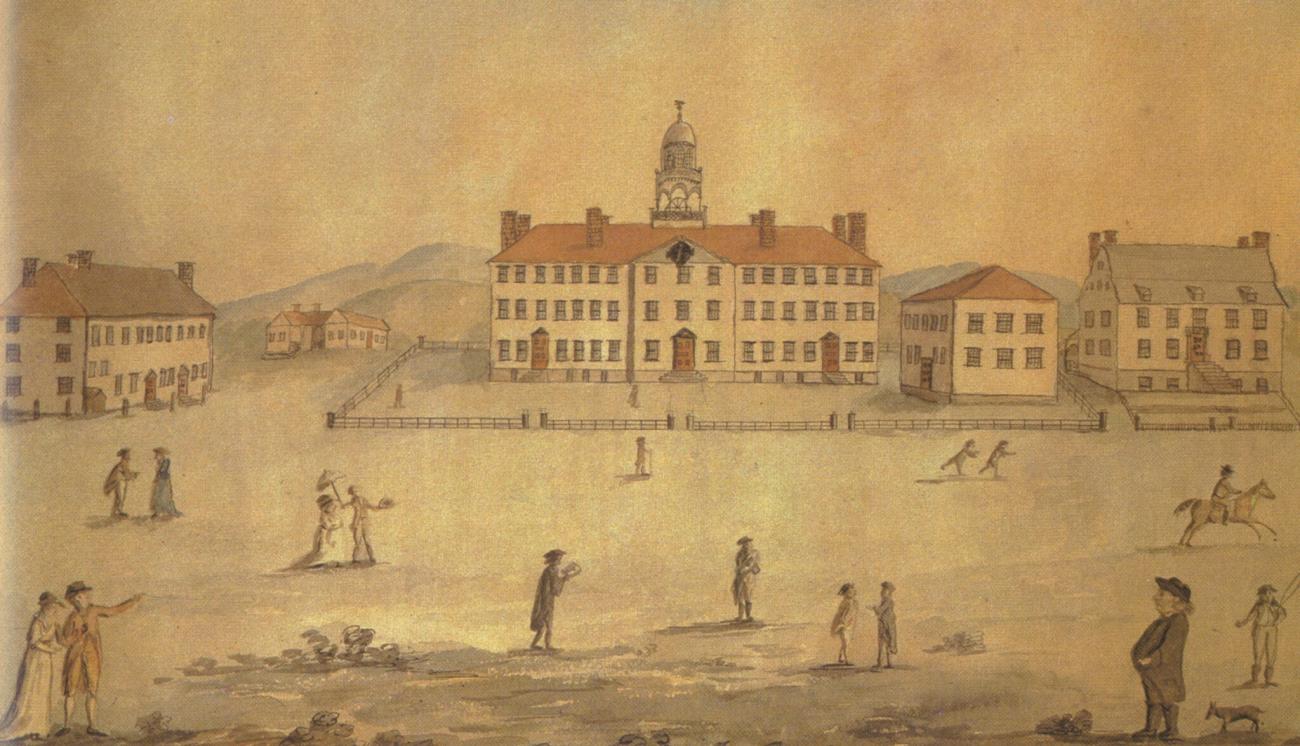

It was no different at Moor’s Indian Charity School. Founded by Eleazar Wheelock in Crank, Colony of Connecticut, in 1754, the school’s purpose was to train Indigenous students to become missionaries to their tribes. Though the enslavement of Indigenous peoples existed in undisguised forms throughout New England, the experience of students at Moor’s points to a more subtle form of bondage, one that demanded domestic and agricultural labor, all disguised as instruction in the European way of doing things.

Wheelock not only used the labor of his students to support the running of his institution, which became the primary source of his livelihood, he held the possibility of debt over the heads of those students who threatened to withhold their work.

Such labor was differentiated between the sexes. Male students mostly worked the farm, yet at one point Wheelock mentions that he intended to apprentice one student to a blacksmith, and another to a carpenter. It is unclear if these latter students were to serve their apprenticeships while at school, though considering the specialization of the trades, it seems unlikely. The practice itself mirrors how some slaveholders would train enslaved Africans in certain trades or skills to fill their own or societal needs.3

Female students, on the other hand, received instruction in reading and writing, but also the various skills involved in European-style housewifery. Unlike male students, who resided at the school, female students lived with, and performed housework for, White families in the surrounding areas, gathering at Moor’s only once a week. In a letter written on May 18th, 1764, by Boston merchant and school supporter John Smith, Smith discusses a visit to Moor’s and notes: “Mr. Wheelock accompanied me a few miles & on passing by one house he said here lives one of my Indian girls.” Like many of the young women at Moor’s, this particular student walked “a few miles” for her one day of schooling.4 Additionally, a student named Miriam Come is recorded by Wheelock to have “kept house for her miss while she was gone on a visit near a fortnight and did it well, understands tending a dairy, and has lately sewed her a pocket.”5 Miriam’s experience shows the level of labor these students were providing under the guise of being educated.

Mary Secutor came from the Narragansett tribe and attended Moor’s from 1763 to 1768. As a woman, she was expected to learn how to read and write and, through her indenturement, learn the skills that would make her a good housewife for her future husband. Evidence of her servitude and increasing unhappiness in her situation is conveyed through several letters she wrote to Wheelock in that time. In a letter from July 28th, 1968, she asks for permission to leave the school. “I am quite discouraged with myself,” she writes,”the longer I stay in school, the worse I am….” Later, she attempts to reason with Wheelock, saying: “It will cost a great deal to keep me here, which will be spending money to no purpose.” That Mary was clearly able to communicate through writing points to her education, yet her letters always reveal deep unhappiness, declining self-worth, and a constant appeal for Wheelock’s approval.

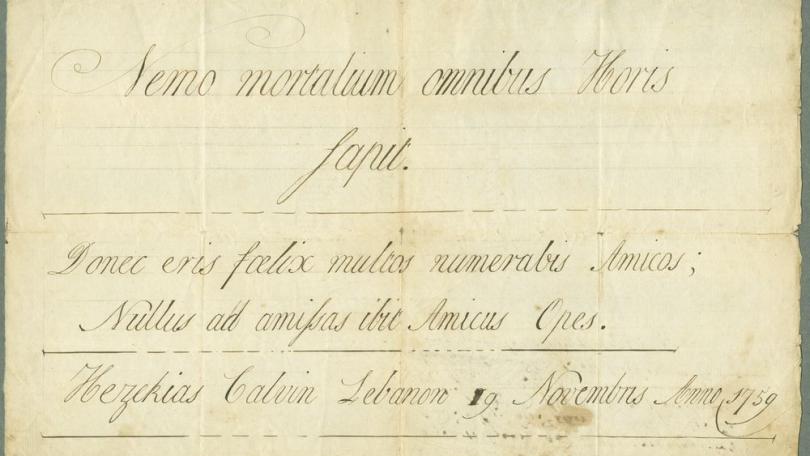

Wheelock’s paternal attitude towards his students is alluded to in several letters, likely coerced, from Secutor to Wheelock confessing drunkenness and rude behavior, and asking for forgiveness. Finally, In a letter from November 16th, 1768, Secutor reveals her lack of desire to marry Hezekiah Calvin, a Delaware Indian and one of Wheelock’s first Indigenous students. Mary writes that she does not want to marry Calvin but “will say nothing untell I hear from you Sir.” Secutor’s servitude exacted more than just physical labor, extending to strictures on behavior, the freedom to stay at or leave the school, or even her right to refuse the man of Wheelock’s choice.

sketch of Moor's Charity School, Lebanon, CT

Handwritten Latin Mottos by Hezekiah Calvin 1759

Daniel Simon was a Narragansett student at Moor’s who would go on to become Dartmouth’s first Native graduate, the only one in Wheelock’s lifetime. In a letter to Wheelock from September, 1771, Simon more directly expresses his dissatisfaction with the work Indian students were required to do. “If we poor Indians shall work as much as to pay for our learning we can go some other place, as good as here…,” he writes, “if I cannot get learning here as I understood I might; I have no business here.”

Sarah Simon, Daniel’s mother, corresponded with Wheelock several times regarding the education of Daniel, as well as a younger son named James. In a letter from Wheelock to Sarah dated June 27, 1768, Wheelock raises the specter of potential debt. “The conditions upon which I take all the English boys in my school are,” he writes, “that if they leave me before they have got their learning, or go into other business afterwards that pleases them better than the Indian Service they shall pay me all the expense of their learning. And I think the reason is as good with respect to your son James.” Despite the fact that James, like all Indigenous students, has been providing labor, Wheelock suggests that James would be indebted to him if he were not to finish his schooling—or continue to provide labor. James’ situation exemplifies the power struggle between Wheelock, the school’s Indigenous students, and their families. The latter not only depended on Wheelock’s connections and recommendations to pursue their goals, but found they could wind up financially beholden to Wheelock if they withheld their labor.

The experience left many students bitter. In a letter written to Wheelock by the White missionary Edward Deake on June 21, 1768, Deake notes that Hezekiah Calvin has been spreading stories among “the Indians in this place” of how Wheelock, among other injustices, used “the Indians very hard in keeping of them to work, and not allowing them a proper privilege in the School.” He goes on to specify that, according to Calvin, “Mary Secuter and Sarah Simon have been kept as close to work as if they were your slaves, and have had no privilege in the school since last fall, nor one copper allowed them for their labor.”

The following year, Wheelock would all but abandon Moor’s and its mission, moving north to Hanover in the Province of New Hampshire to found Dartmouth College.

Notes:

1. Margaret Ellen Newell, Brethren by Nature : New England Indians, Colonists, and the Origins of American Slavery. 1st ed. (Ithaca, New York ; Cornell University Press, 2015), 5-6.

2. Ibid, 11-12.

3. Eleazar Wheelock, A Plain and Faithful Narrative of the Original Design, Rise, Progress and Present State of the Indian Charity-School at Lebanon, in Connecticut, (Boston: Printed by Richard and Samuel Draper, in Newbury-Street, 1763), 32-34.

4. James Dow McCallum and Eleazar Wheelock, The Letters of Eleazar Wheelock’s Indians, (Hanover, N.H: Dartmouth College Publications, 1932), 75.

5. Eleazar Wheelock to John Brainard, Mss 761606.1, Rauner Special Collections Library, Dartmouth College.