In the 1740s, Eleazar Wheelock was a newly ordained minister of the Second Congregation in Lebanon, Colony of Connecticut. Caught up in the Great Awakening, a religious revival that swept the colonies in the mid-18th century, Wheelock was a New Light minister and a radical by Anglican standards.1 He was also unhappy with his compensation,2 and so began taking on pupils to tutor.3

One of these pupils was Samson Occom, a member of the Mohegan tribe. Occom’s motivations for seeking an education from Wheelock may never truly be known, but in a biographical statement he professed a desire to read, particularly the Bible, and to be able to teach his “brethren” to read. What is known is that he found the Christian religion through the Great Awakening, remained devout throughout his life, and devoted himself to supporting his tribe and other Indigenous peoples in the northeast.4

Wheelock was inspired by Occom, an apt and diligent student, to develop the idea of training Indigenous peoples as ministers to spread the gospel and thereby assimilate the Indigenous population.5 While the the concept of assimilation through education and religion was not original—John Eliot, who is credited with printing the first Bible in North America, had similar ambitions almost 100 years before Wheelock—the idea of anointing Native Americans as ministers to preach the gospel to their own peoples was fairly new.6

If Wheelock’s work was part of a long European-American agenda to erode and destroy Indigenous cultures, his religious fervor was such that he very literally believed he was saving souls. He also believed in the intellect of his Native American students, and the education that Wheelock provided to Occom, and that he would go on to offer to other Indigenous peoples, was on par with or exceeded that which many European Americans were able to obtain at the time. (But at what expense? Both Eliot’s and Wheelock’s projects eventually led to one of the most unfortunate chapters of our country’s history: the forcible removal of Indigenous children to off-reservation boarding schools in the latter part of the 19th century.)7

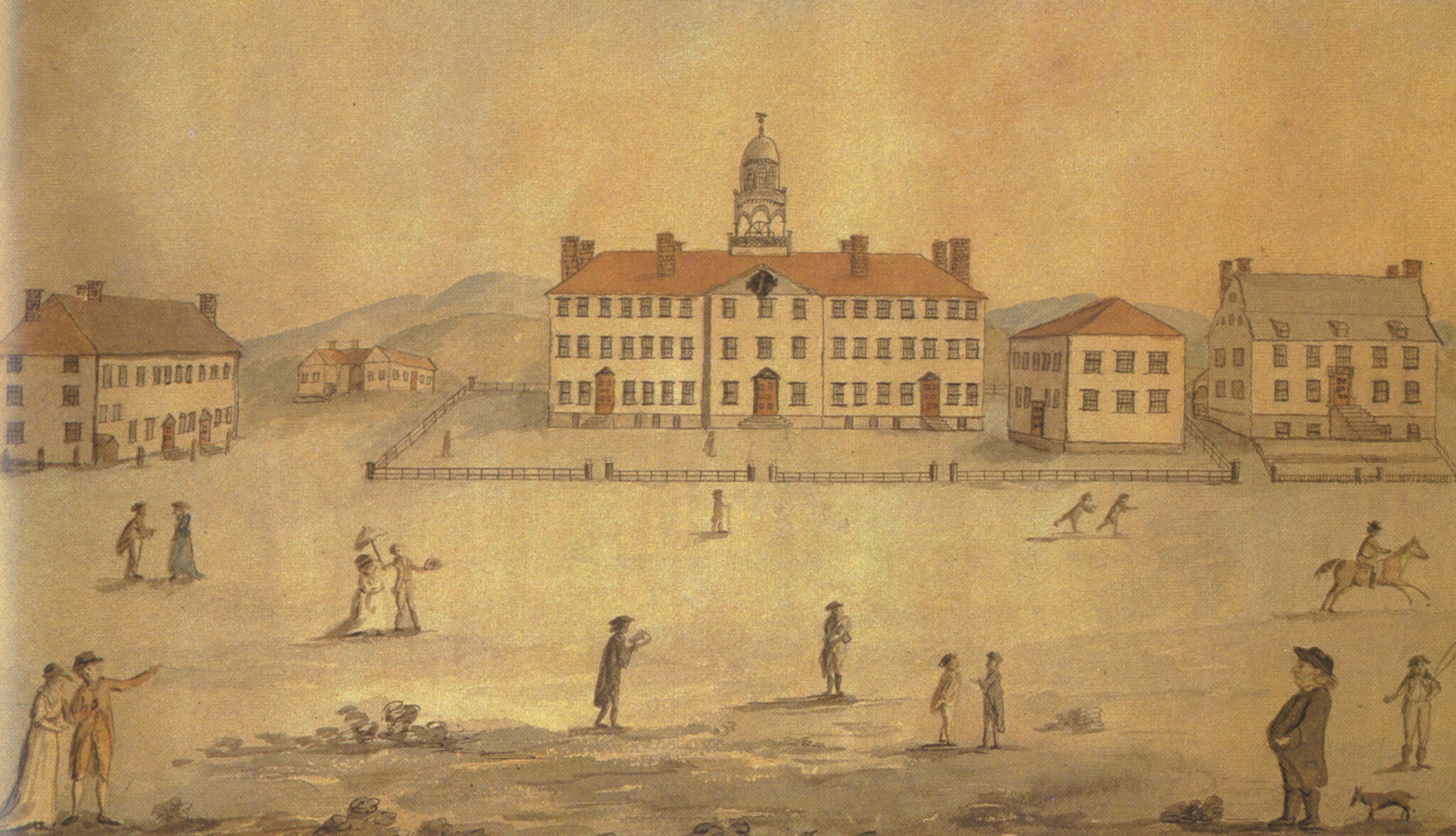

Based on his success with Occom, and likely the school that Occom started on Montauk, Wheelock created what became known as Moor’s Indian Charity School, specifically aimed at educating and converting Indigenous boys and girls to Christianity. From the beginning, Wheelock struggled to make the school solvent. While he managed to get some support from the Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge (SSPCK), which had established commissions or boards in most of the New England colonies, his frequent clashes with the Boston Board of SSPCK resulted in inconsistent and ultimately insufficient funding.8

Wheelock, ever the strategist, knew that the greatest wealth did not reside in the colonies. In 1766, he sent Occom, accompanied by the European-American minister, Nathanial Whitaker, to England and Scotland to raise money for the school.9 It is likely that Wheelock was also trying to stifle Occom’s support of his people in the Mason Land Dispute, a Connecticut conflict that had already gotten both Wheelock and Occom into hot water.10

In England, George Whitefield, father of the Great Awakening,11 took Occom under his wing and introduced him to London society. Occom met with King George III12 and, ironically, even managed to lobby Parliament on behalf of his people in their land dispute.13 He also traveled widely, preaching across both England and Scotland, all while taking up collections for Wheelock’s school. In the end, his work raised £12,026, a very substantial sum at the time.14

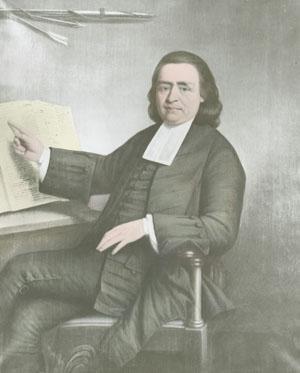

Samson Occom (1723-1792), founder of Dartmouth College

Memorial to Samson Occom, near Moor's Charity School in present-day Colombia, CT

Yet, when Occom returned to Connecticut in 1768, he found that, contrary to his promises, Wheelock had not adequately cared for Occom’s family in his absence. Occom also discovered that Wheelock had abandoned the idea of a school for Indigenous peoples and had instead used the funds that Occom raised to found a college in the Province of New Hampshire, which was at the time on the distant frontier of colonial settlement and situated in Abenaki territory, an area unfriendly to the Mohegan.15

Occom and Wheelock had a bitter falling out, and Occom never set foot on the campus of the college that he had unknowingly raised the money to found. Moor’s School continued until 1849 as a feeder school for the college. While most of the students who attended Moor’s were White, a few Indigenous and Black students matriculated.16 It would, however, be 200 years before a substantive number of Indigenous students were even admitted to Dartmouth.

Occom went on to gain significant notice as a minister after he preached a famous sermon at the execution of Moses Paul, an Indigenous man who was hanged for the murder of a White man. Over his lifetime, Occom spoke eloquently against societal ills, the poor treatment of Indigenous peoples, and slavery. Eventually, he concluded that the White settlers were hypocrites and unchristian; he also decided that, despite his best efforts and beliefs, Indigenous peoples could not coexist with settler society. In 1789, he led a group of Indigenous Christians to Oneida country in New York state, and founded a community called Brothertown. In the 1830s, the community resettled in Wisconsin, where it still exists today.17 On April 27, 2022, the papers and materials of Samson Occom were repatriated to the Mohegan Tribe.

Notes

1. Leon B. Richardson, History of Dartmouth College (Hanover: Dartmouth College Publications, 1932), 20-23.

2. Richardson, 16-17.

3. David McClure and Elijah Parish, Memoirs of the Rev. Eleazar Wheelock, D.D. (Newburyport: E. Little & Co., 1811), 16.

4. Samson Occom, Autobiography, undated.

5. A Plain and Faithful Narrative of the Original Design, Rise, Progress and Present State of the Indian Charity-School at Lebanon, in Connecticut (Boston: Richard and Samuel Draper, 1763), 16-18.

6. Richard W. Cogley, “John Eliot and the Origins of the American Indians,” Early American Literature 21. 3 (Winter 1986/1987): 213-214.

7. Robert Middlekauff, "Education in Colonial America," Current History 41.239 (July 1961), 7-8.

8. A Plain and Faithful Narrative, 10, 15.

9. Richardson, 46-47, 53.

10. Richardson, 53.

11. It is notable that while Whitefield advocated for the humane treatment of enslaved people, he was not against slavery and was the recipient of a plantation in South Carolina, purchased for him by the Byrans family as a way to raise funds for an orphanage that Whitefield had started. See: Allan Gallay, "The Origins of Slaveholders' Paternalism: George Whitefield, the Bryan Family, and the Great Awakening in the South," Journal of Southern History 53.3 (Aug. 1987), 379.

12. Samson Occom, Journal, 1765 November 21.

13. Joanna Brooks, ed. Samson Occom: Collected Writings from a Founder of Native American Literature, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 19-20.

14. Richardson, 66.

15. Brooks, 20-22.

16. Colin G. Calloway, The Indian History of an American Institution : Native Americans and Dartmouth (Hanover, N.H: Dartmouth College Press, 2010), xviii, 198-203.

17. Brooks, 4-5.