The papers and materials of Samson Occom, stewarded by the Dartmouth Library for many years, were repatriated to the Mohegan Tribe on April 27, 2022.

About

About

The repatriation of the papers and materials of Samson Occom marks an important moment in the history of Dartmouth College and of the Mohegan people, recognizing and celebrating not only Samson Occom’s critical role in the establishment of the College, but also honoring Occom by returning to his homeland materials that have a deep spiritual meaning to the Mohegan Tribe.

The repatriation ceremony, held on April 27, 2022, was both sobering and moving. As an important step in the restorative justice owed to the Mohegan Nation, it was ultimately hopeful, setting us on a new path in our linked histories. Recent news stories from Dartmouth and Mohegan have noted the importance of this event, and images, video, reflections, and remarks from the repatriation ceremony provide additional details.The purpose of this website is to document and contextualize the repatriation.

In the sections below we explore some of the processes involved, including the development of the Occom Circle project, a partnership between the Dartmouth Library and the Hood Museum of Art focused on developing new approaches for stewarding cultural heritage materials, and advocacy from Dartmouth’s Native American Visiting Committee that led to the recent repatriation.

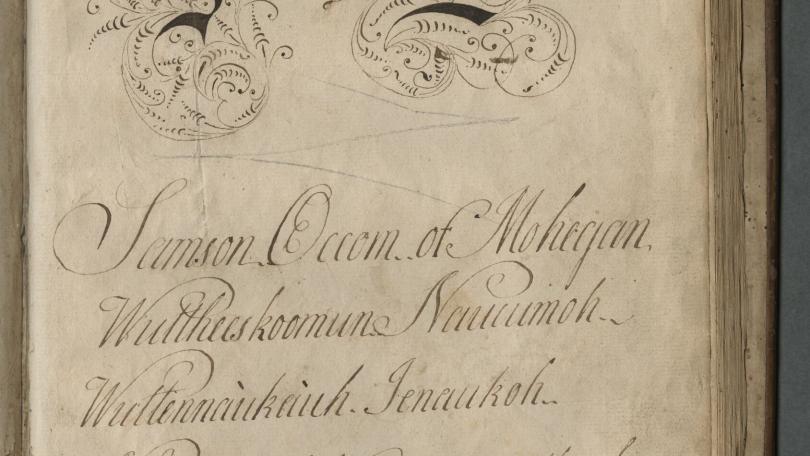

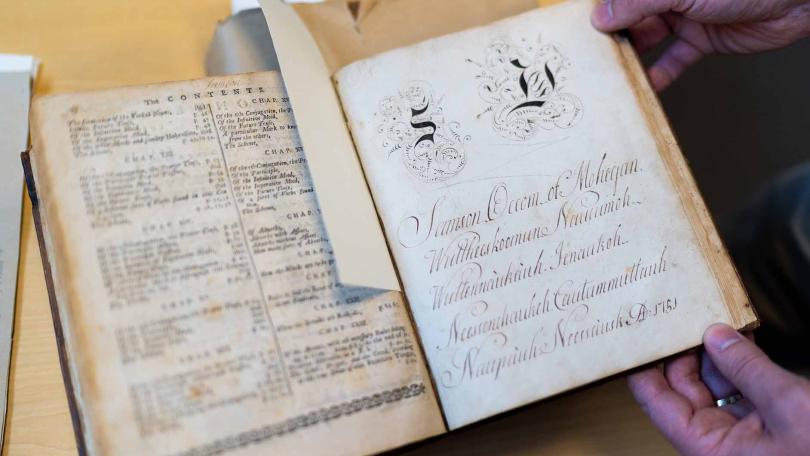

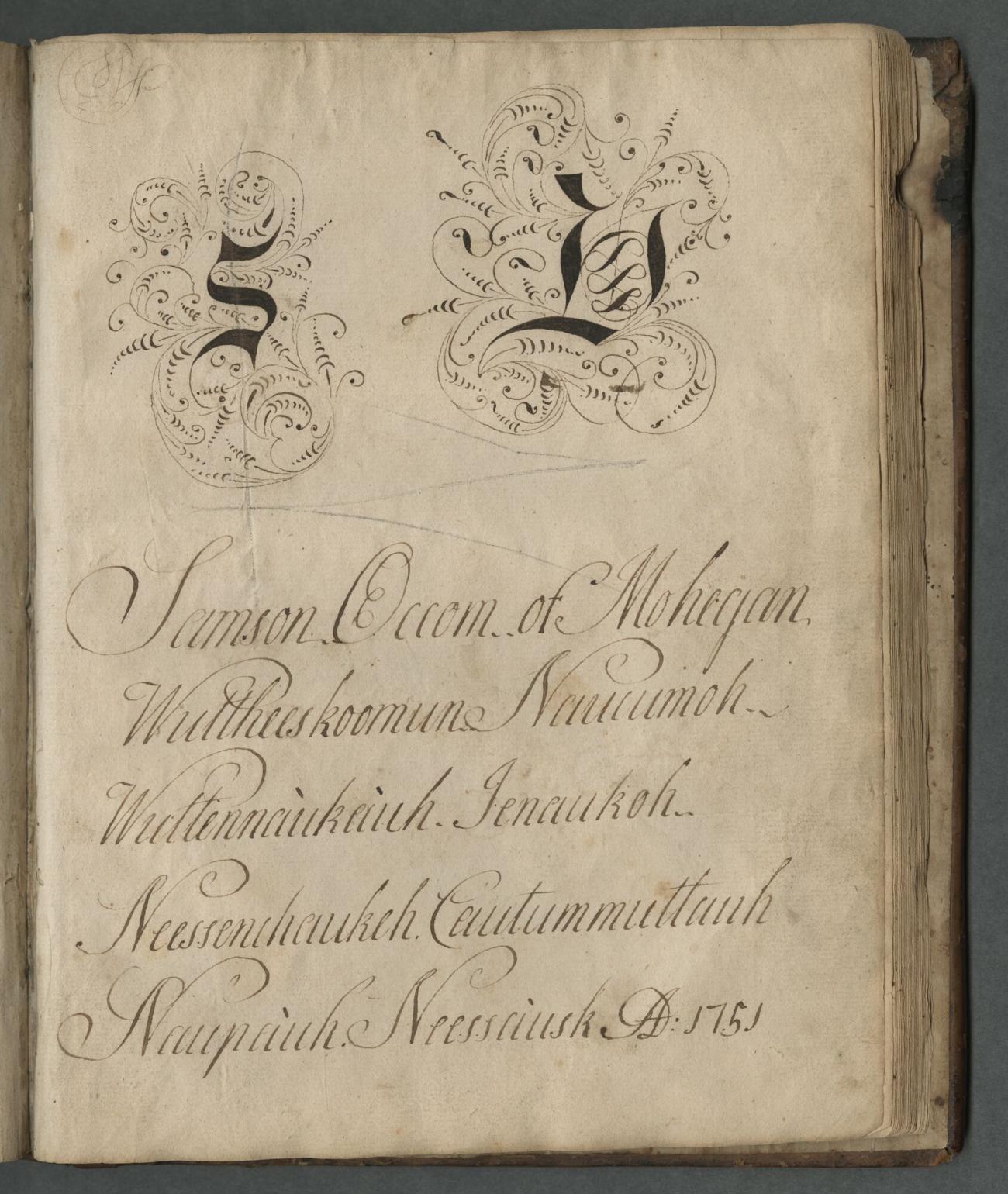

Occom's Hebrew textbook with Occom's name written in English, Hebrew, and Mohegan | photo by Julia Levine

History, Materials, Work, & Partnerships

A Founder of Dartmouth College

A Founder of Dartmouth College

Samson Occom was a member of the Mohegan tribe and believed to be a direct descendant of its great chief Uncas. He was born near colonial New London, Connecticut in 1723, and was converted to Christianity at age eighteen during the Great Awakening. At twenty, he went to study for four years at the Lebanon, Connecticut, home of Congregational minister Eleazar Wheelock. Occom was a remarkable student and scholar, and became one of the first Native writers published in the colonies, while always maintaining his identity as a Mohegan and his commitment to the welfare of Native peoples in the Northeast. For the next twelve years, he served as an effective educator to the Montauk Indians of Long Island, and was ordained a Presbyterian minister in 1759. When he returned to Mohegan, he became an eloquent and popular spiritual leader and teacher, also supporting the Mohegan Tribe’s lawsuits against the Colony of Connecticut, which threatened to take ownership of ancestral lands.

Occom also supported the efforts of Moor’s Indian Charity School to educate Native children from the region, traveling across England and Scotland from 1766-68, preaching to rapt audiences, meeting leading figures, and raising money for the school. Occom was fantastically successful: he raised more than £12,000 (about $2.4 million today), including support through the Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge. Upon his return, however, he was disappointed to find the school relocated to a royal grant in New Hampshire and renamed Dartmouth College, which the funds he raised helped to establish. Occom then became an outspoken advocate for Indian rights, a conviction reinforced by the decision in 1773 of the Mason Land Case against the Mohegan Tribe. To address the Mohegan Tribe’s poverty and powerlessness, Occom helped found Brothertown, formed from various tribes, which eventually settled in Oneida Country in upstate New York. Occom moved there with his family in 1789, leaving a portion of the Mohegan Tribe in Connecticut. Occom died in 1792 in New Stockbridge, New York. As the Mohegan Tribal website concludes: “His legacy for the Mohegan people who remained in Connecticut was a reputation for being Christianized, which helped them avoid later relocation.”

Occom never set foot at the school that became Dartmouth College, and between 1769 and 1970 Dartmouth graduated only 20 Native students. It wasn’t until 1970 that then-President John Kemeny “sought to turn this point of pain for Occom and, by extension, the Native community, into a point of pride,” according to Dartmouth President Hanlon. Part of this refocus was the founding of what is now Dartmouth’s Department of Native American and Indigenous Studies in 1972; more than 1,200 Native American students have graduated from Dartmouth since then.

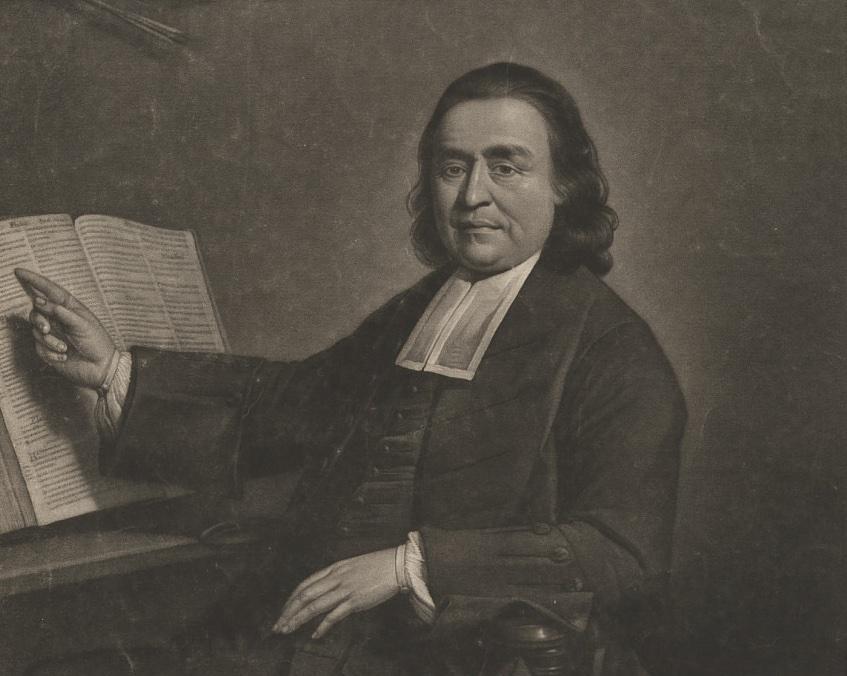

Mezzotint of Samson Occom by Jonathan Spilsbury, after a portrait by Mason Chamberlin, 1768. National Portrait Gallery, public domain.

Repatriation/Rematriation

Sarah Harris speaks at the Occom papers repatriation ceremony. Dartmouth President Phil Hanlon seated to her left. Photo by Eli Burakian '00.

Repatriation/Rematriation

The repatriation of Occom’s papers marks an important, reparative step in the relations between Dartmouth and the Mohegan Tribe. On the occasion of the repatriation, President Hanlon offered that “it has taken far too long for these papers to be returned to where they’ve always belonged, but they are here now, accompanied by the spirit of Samson Occom that lives on in them.”

In her remarks during the ceremony, Sarah Harris, ’00, vice chairwoman of the Mohegan Tribal Council and a member of Dartmouth’s Native American Visiting Committee, described a recent conversation with other Indigenous alumni in which they each described a struggle to feel as if they truly belonged at Dartmouth as undergraduates.

“The funds that established Dartmouth College were intended for the education of Indian people—if anyone should feel as though they belong at Dartmouth, it’s us,” she said. “Telling the truth of the College’s founding honors and gives life to Occom’s accomplishments and shows Native students that they’re foundational to the school and not just an afterthought. Truth—especially when it’s painful and difficult—is the birthplace of real meaningful change.”

Repatriated Materials

Repatriated Materials

Preparing the documents and materials for repatriation required months of detailed work: compiling lists of every single item, extracting each one from the archival collections, and getting them ready for re-digitization before relocating all the materials to Mohegan.

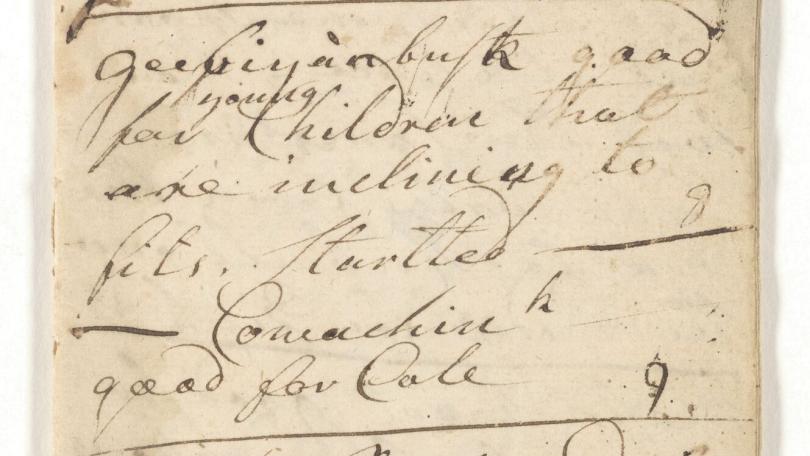

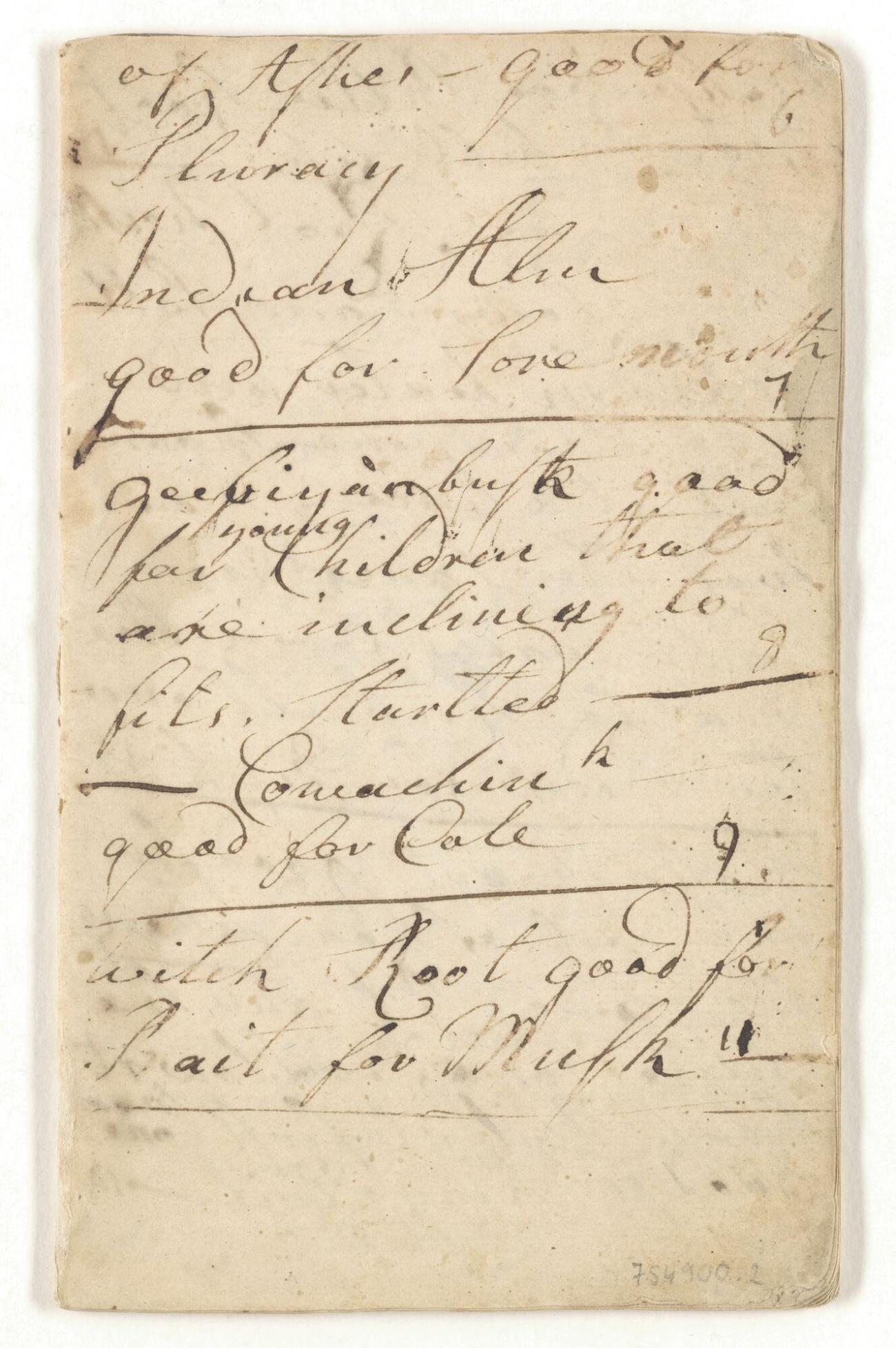

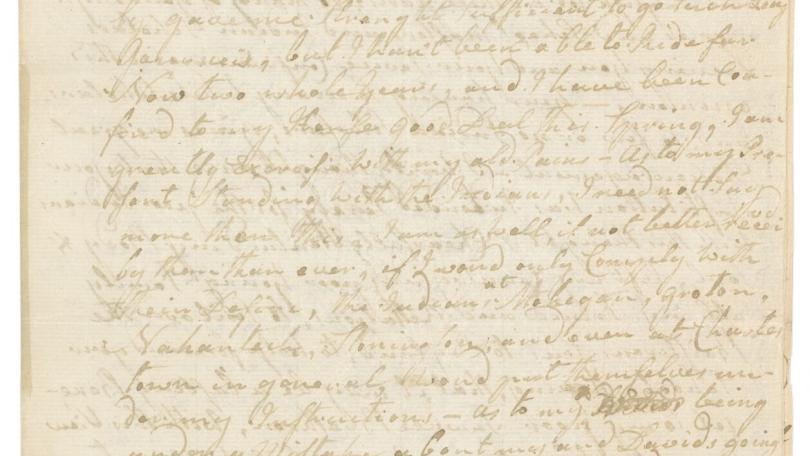

The Occom materials that were returned to Mohegan comprise a wide variety of documents and books. One of the most stunning and possibly significant of these is a Hebrew primer owned by Occom in which he inscribed his name in English, Hebrew, and Mohegan. This is likely the first time the Mohegan language appears in written form. In addition, the collection also includes two versions of Occom's autobiography and a page of herbal remedies describing the medicinal uses of local plants and herbs. Among Occom's letters are personal missives to his wife during his absence in England while he was raising funds for what was supposed to be a school for Native students. Among the most important documents is the scathing letter that Occom penned to Wheelock when he discovered that Wheelock had misappropriated the funds that Occom had raised in England and applied them to Dartmouth College instead. This letter clearly expresses Occom’s sense of betrayal and deep disappointment in Wheelock, but also spells out the horror he feels at being made to appear to be an accomplice in an act of deception.

These materials now reside at the Mohegan Cultural Preservation Center, alongside other relevant collections and relations.

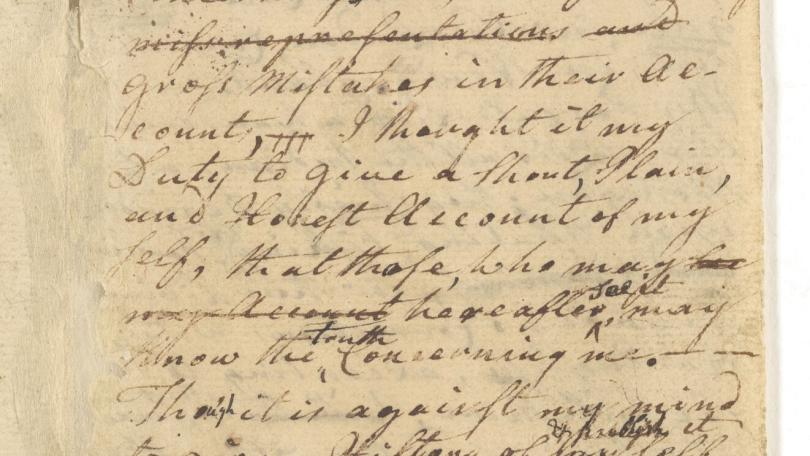

Letter from Samson Occom to Eleazar Wheelock, July 24, 1771. Occom notes his disinclination to go into the wilderness, and complains bitterly of having been used as an agent and a curiosity in England to collect money for the college. He points out that there are no Indians at the school at present (except "two or three Mollatoes") and that this confirms his suspicion that Wheelock was scheming all along to use the charity for whites.

Selected Items from the Repatriated Material

One of the most stunning and possibly significant of items is a Hebrew primer owned by Occom in which he inscribed his name in English, Hebrew, and Mohegan. This is likely the first time the Mohegan language appears in written form.

One of the most stunning and possibly significant of items is a Hebrew primer owned by Occom in which he inscribed his name in English, Hebrew, and Mohegan. This is likely the first time the Mohegan language appears in written form.

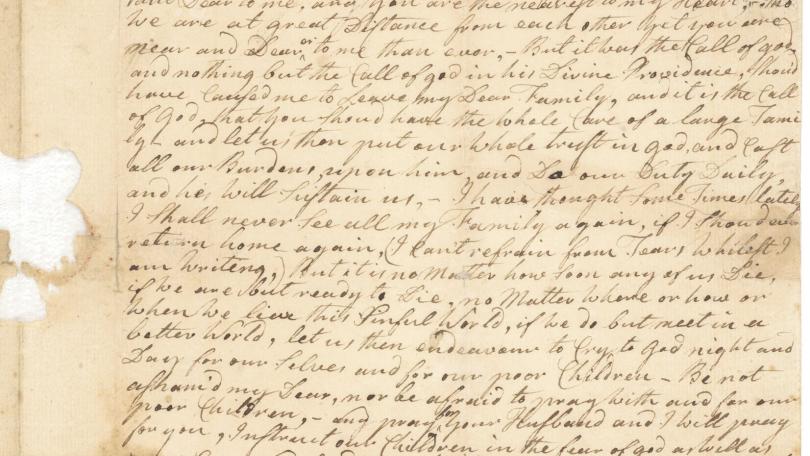

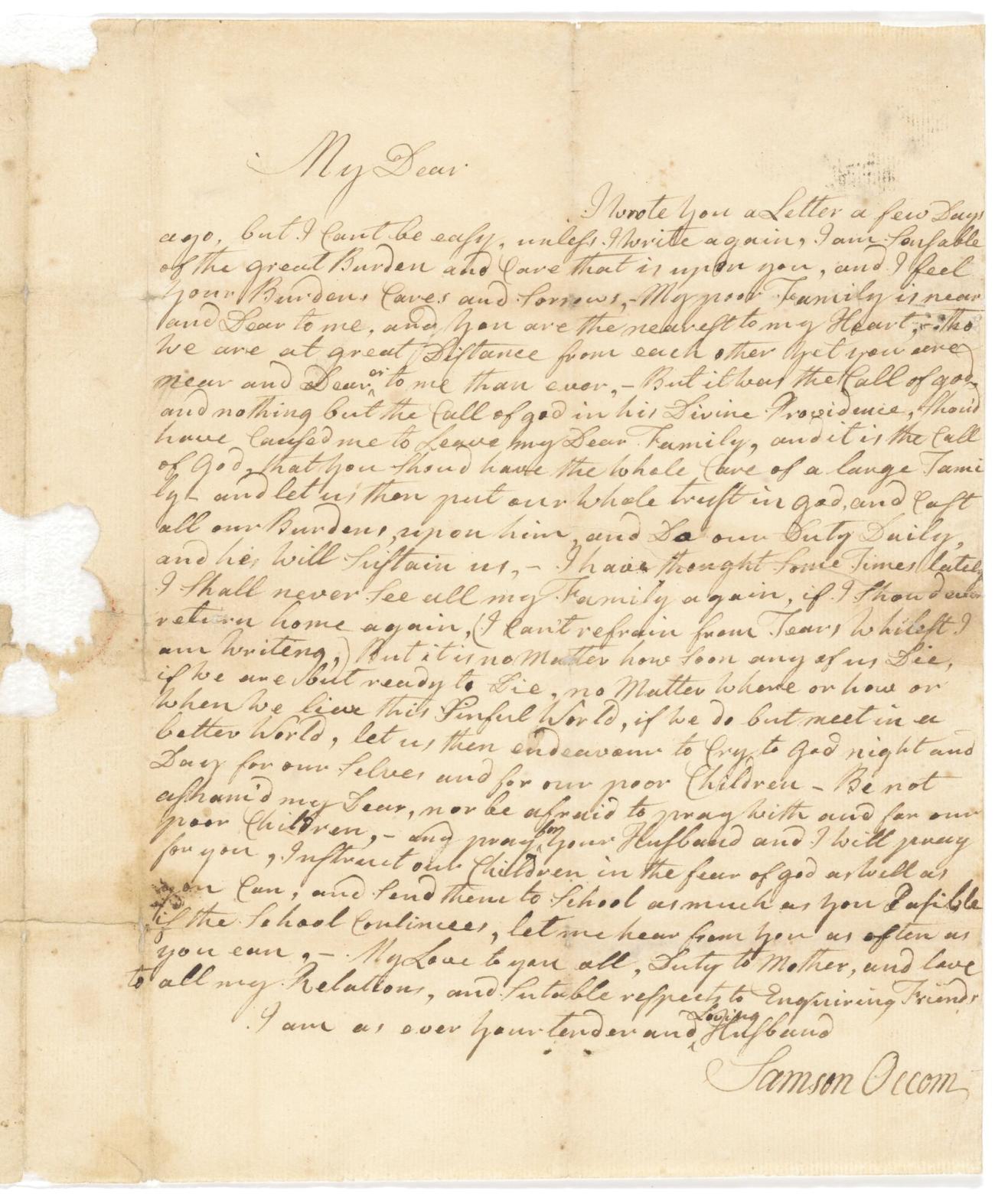

Samson Occom writes an emotional letter to his wife acknowledging the burden of caring for their children in his absence. He stresses his feelings for his family and the importance of faith and his ministry.

Samson Occom writes an emotional letter to his wife acknowledging the burden of caring for their children in his absence. He stresses his feelings for his family and the importance of faith and his ministry.

Provenance

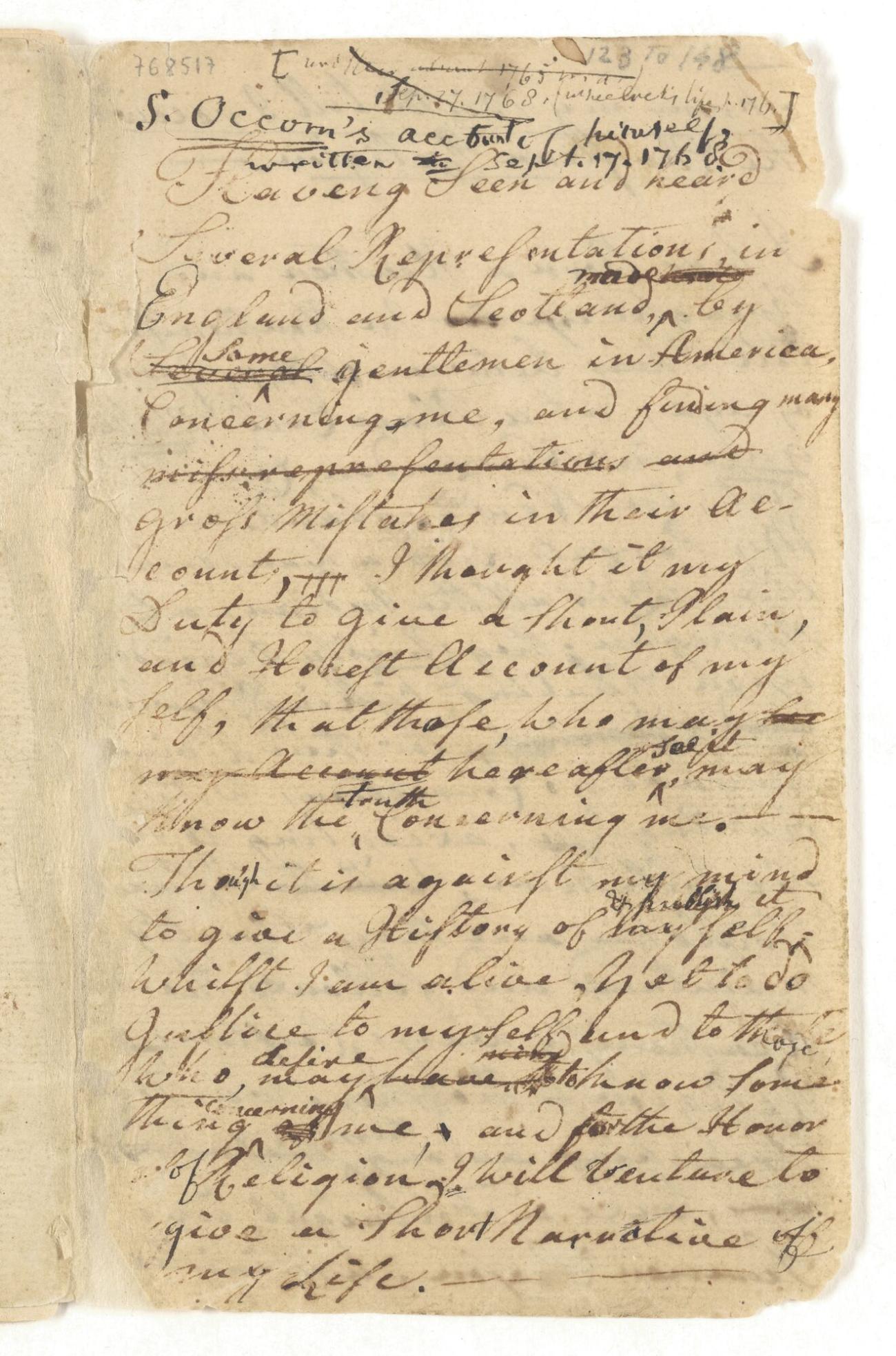

Occom writes a second draft of his autobiography. Occom's text is overwritten by another hand in a darker ink.

Provenance

According to College Archivist Peter Carini, there are three possible sources for the items that comprise the Occom papers, though the exact provenance of the documents is unclear.

In several instances, Occom’s writing in his journals and autobiography have been overwritten by another hand in a significantly darker ink. The hand appears to be 19th century and looks a great deal like that of the journalist and historian William Leet Stone, Jr. One extant letter in the Library’s collection from Stone Jr. refers to a letter he gave to the College in 1866 that was by the “first Indian Scholar (or Student) that, I believe, entered your College.” A letter by Occom is referenced in an article in The Dartmouth in 1867, but there is no way to know if it is the same letter given by Stone Jr., or if others had been acquired earlier or around the same time. It is possible that Occom’s papers, or a significant number of them, fell into William Leet Stone, Sr.’s hands after Occom’s death. Stone Sr. lived in the same area as Occom and in addition to a book on the Mohawk chief Joseph Brant (also a student of Wheelock), Stone Sr. also wrote a book on the Mohegan Tribe in 1842 titled Uncas and Miantonomoh.

Another possible source of these documents may have been Samuel Kirkland. Kirkland was Eleazar Wheelock’s most famous Anglo American student. He conducted a 40-year mission to the Oneidas and founded Hamilton College. Kirkland was still working among the Oneida when Occom died in Stockbridge, New York, in 1792, and may have persuaded a family member to part with the papers.

It is also just as likely that the papers came to Dartmouth in small batches and individual donations over the course of many years from a wide range of sources. It is also possible that they came through some combination of all of these routes. It appears that the materials related to Occom were in Dartmouth's possession prior to the establishment of the College Archives, in 1928, as the papers are referenced in two articles in The Dartmouth in 1926 and 1927.

Just as the repatriation of these papers and materials is vital to the ongoing relationship between Dartmouth and the Mohegan Tribe, it is also important to rigorously consider the provenance of the materials. For centuries, the practices and processes of cultural heritage organizations have emphasized building collections, and an honest reckoning of such practices must be part of contemporary stewardship.

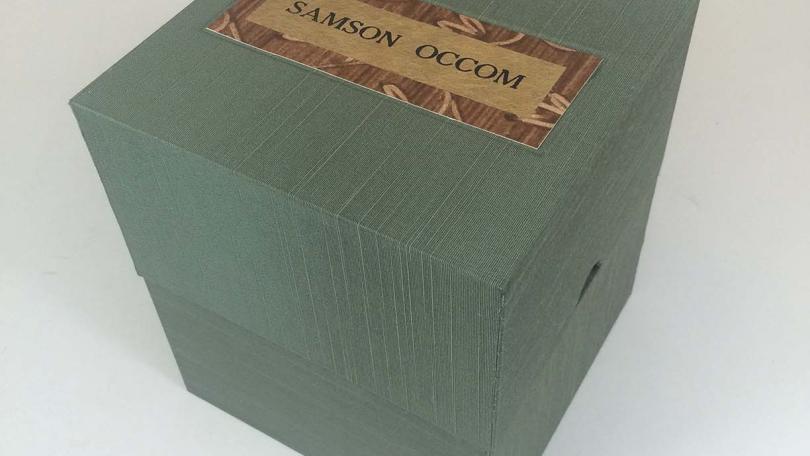

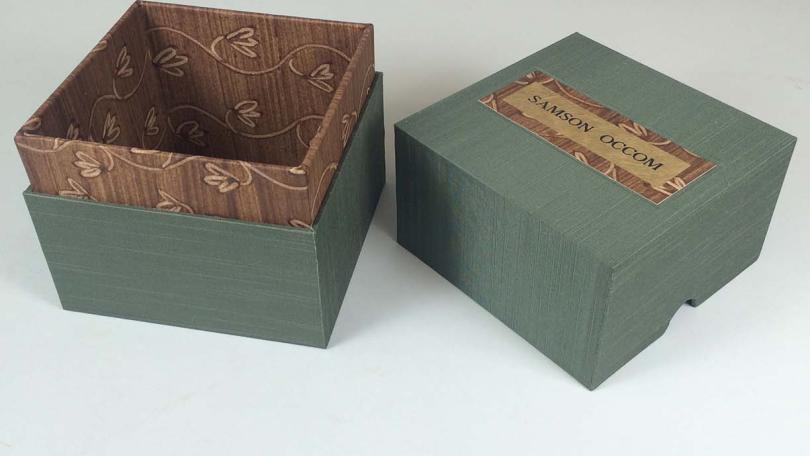

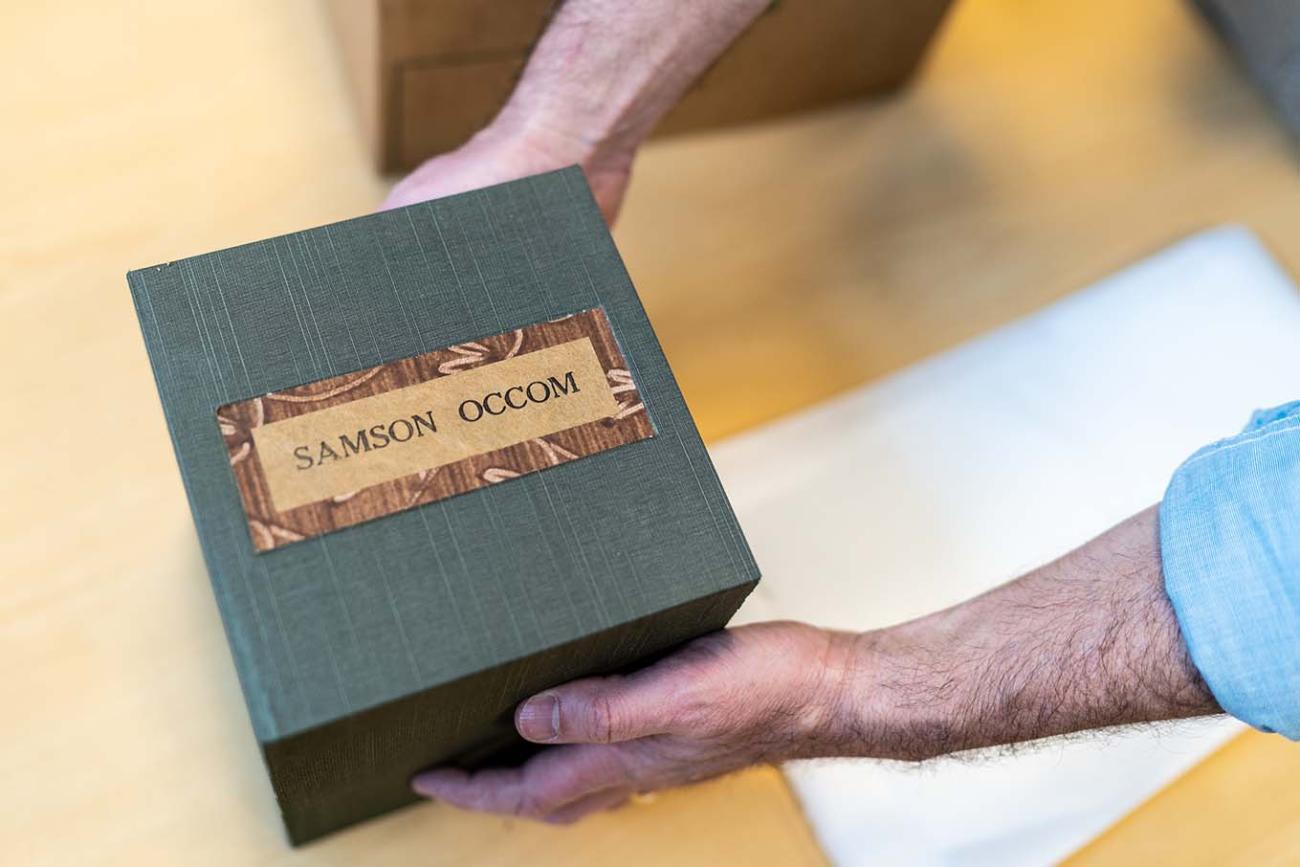

Presentation Box

Presentation Box

In order to carefully protect and convey the Occom materials, Dartmouth Library's Assistant Conservator Lizzie Curran crafted a beautiful, handmade ceremonial presentation box for the occasion.

Lizzie created the paste paper (a traditional method of decorating paper to cover books) that lines the interior of the box using a pattern that Samson Occom carved into a box of his own. The organic, undulating pattern represented Occom’s journey across the Atlantic as well as the movement of his tribe from Connecticut to New York. The use of the paste paper in the box is intended to represent the continued journey of his legacy.

The exterior of the box is covered with sage green silk bookcloth, and a paper label for the lid was stamped in gold.

Dartmouth President Philip J. Hanlon ’77 presents Mohegan Tribal Council Chairman James Gessner Jr., center, and other tribal leaders with a box containing some of Samson Occom’s papers at a ceremony in Uncasville, Conn., Occom’s Mohegan homeland, on April 27, 2022. Standing at left is Mohegan Tribal Council Vice Chairwoman Sarah Harris ’00, a member of Dartmouth’s Native American Visiting Committee. Photo by Eli Burakian '00.

Selected Images of the Presentation Box

Re-Digitization & Website Redesign

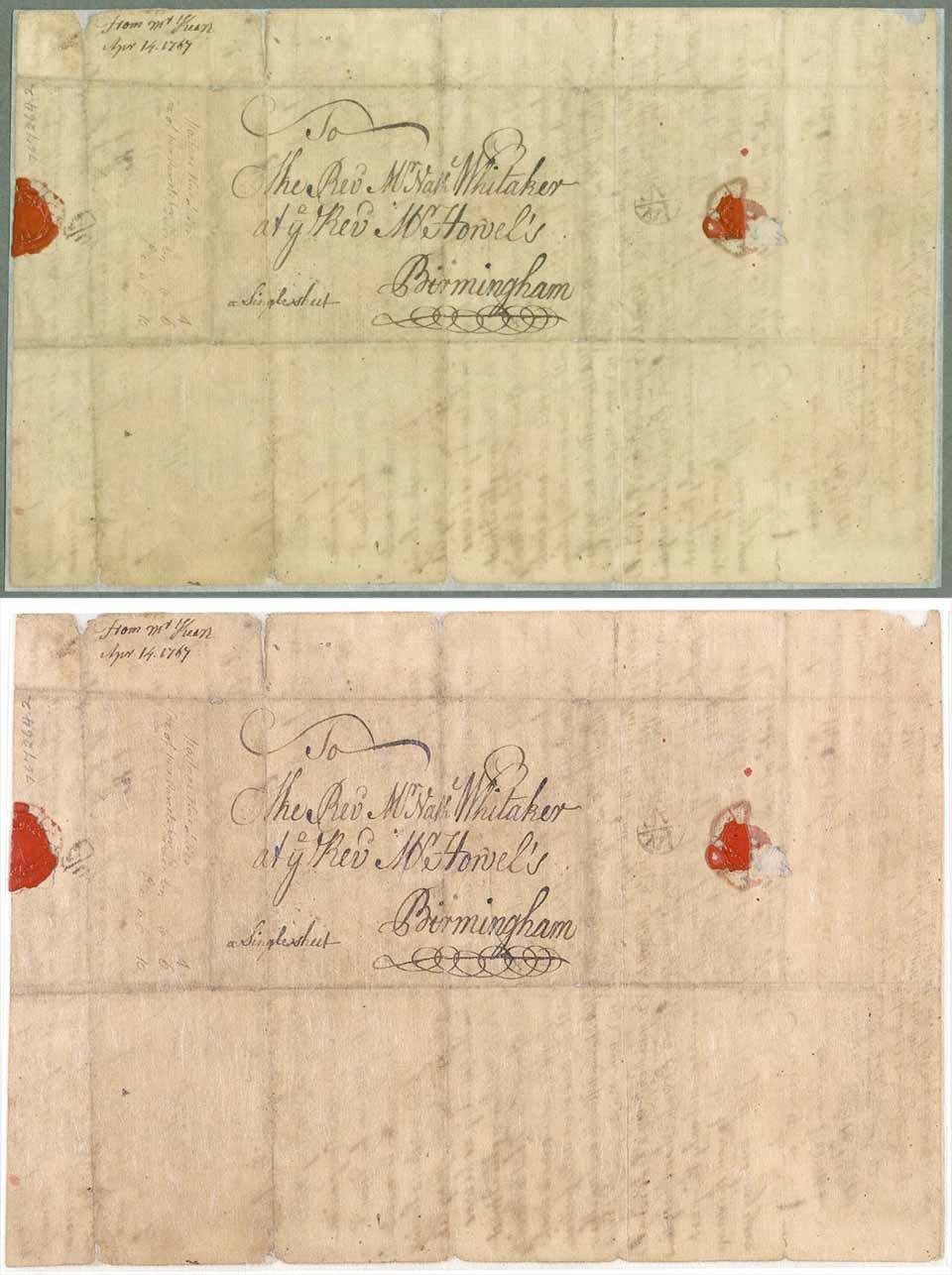

A document from the Occom collection showing the enhancements from the re-digitization. Before (top) and after (bottom).

Re-Digitization & Website Redesign

Although the physical items that make up the Occom papers will reside at the Mohegan Cultural Preservation Center, the Dartmouth Library, in agreement with the Mohegan Nation, will continue to steward and preserve a digital edition of Samson Occom’s papers, The Occom Circle. In order to provide digital access to the highest quality digital representations, the Digital by Dartmouth Library (DxDL) team, in collaboration with members of the Dartmouth Library Technology Group and other Dartmouth Library staff, worked diligently over the past few months to refresh and re-envision the digital Occom collections for the repatriation.

Many Occom papers had been shared over the past decade through a digital scholarly project known as the Occom Circle, a partnership between Professor of English Ivy Schweitzer, the Dartmouth Library, and a number of student and other contributors. Library staff migrated the original Occom Circle website to the Library’s instance of the web development platform Drupal and rewrote code to refresh the look and feel of TEITexts, DxDL’s collections platform for digitized manuscripts. Working with Professor Schweitzer, one of the project’s original directors, the Library updated the language and design of the site’s front pages. Work on the site’s design and content was framed by the Library’s commitment to the responsible and thoughtful stewardship of digital Indigenous materials, based on conversations with the steering committee of the Advancing Pathways for Cross-Institutional Collaboration Mellon Grant project, which is focused on Indigenous collections in the Dartmouth Library and the Hood Museum of Art.

Library staff also re-digitized Samson Occom’s documents to the highest level of quality available to the team. Staff analyzed the existing digital images using file analysis tools and documentation of workflows and standards from the original project. Improvements in both equipment and workflows meant that image quality could be significantly improved through re-digitization. This project motivated the team to further improve its imaging standards. The DxDL team invested in new software and color targets, and staff worked with leaders in the field of digital image analysis to develop color profiles that brought the digitization outputs into compliance with the highest best-practice standards for digitization. Expanding on previous enhancements in digital production workstations and workflows, Library staff imaged, processed, and quality checked over 1500 pages in four weeks.

Through this careful, thoughtful, and collaborative work, the Dartmouth Library will continue to preserve, honor, and make available the words of Samson Occom, which you can view right now at the Occom Circle website.

Our Mohegan Library and Museum Colleagues

Our Mohegan Library and Museum Colleagues

Perhaps the most crucial aspect of the repatriation process has been the opportunity to develop relationships between the professional teams at Dartmouth and Mohegan.

Over the course of a series of reciprocal visits, members of the Dartmouth community had the opportunity to get to know library and museum colleagues at Mohegan. Madeleine Hutchins currently works at the Tantaquidgeon Museum and gave Dartmouth staff a personal tour on a visit in April. On that occasion, staff also met David Freeburg (librarian/archivist), Jason LaVigne (programs coordinator and tribal historian), Stacy Dufrene (museum operations manager), and Greg Chapman (Mohegan Village tradition specialist). Building on these initial connections, Dartmouth staff have also invited our Mohegan colleagues to visit the Dartmouth Library and the Hood Museum of Art.

The Samson Occom collection is now cared for by David and his colleagues. In order to request access to the collection, please contact:

David Freeburg

Archivist/Librarian

The Mohegan Tribe | Library & Archives

13 Crow Hill Road | Uncasville, CT 06382

860-862-6881

dfreeburg@moheganmail.com

David Freeburg, Madeleine Hutchins, and Jason LaVigne in front of the Mohegan Church in Uncasville, CT. Photo by Sue Mehrer.