Enslaved Black people have been documented in the New England colonies as early as 1638.1 In 1774, the overall population of Blacks in colonial New England reached its height, with a total of 16,034 individuals. At that time, enslaved Black people made up 2.4% of the overall population2—slight in comparison to the Southern colonies, where, as early as 1750, enslaved Black people made up 37.9% of the population.3

It may come as a surprise, however, that most New England clergymen, lawyers, and merchants enslaved at least one person;4 and the region’s crucial role in the transatlantic slave trade is often overlooked. Its trees provided the timber and masts for British ships that departed its seaports, transporting provisions from its waters and fields to sustain distant plantations. These same ships returned laden with both the enslaved and with the slave-produced bales of cotton and bags of sugar that New England mills wove into cloth and distilled into rum.

Dartmouth founder Eleazar Wheelock’s home colony, Connecticut, was not a center of the slave trade on the scale of either the Rhode Island or Massachusetts Bay colonies, but its enslaved population increased rapidly from 1,000 in 1740, to 4,300 in 1761. By 1774, when the enslaved population numbered 5,085, Connecticut was the single largest slave-holding colony in New England. This increase in the enslaved population is likely due to the concentration of wealth in Connecticut at the time, which made unemployment very low and thus made it difficult to fill positions with either free laborers or indentured servants. In addition, Connecticut had many large farms that would have required significant labor to run.5

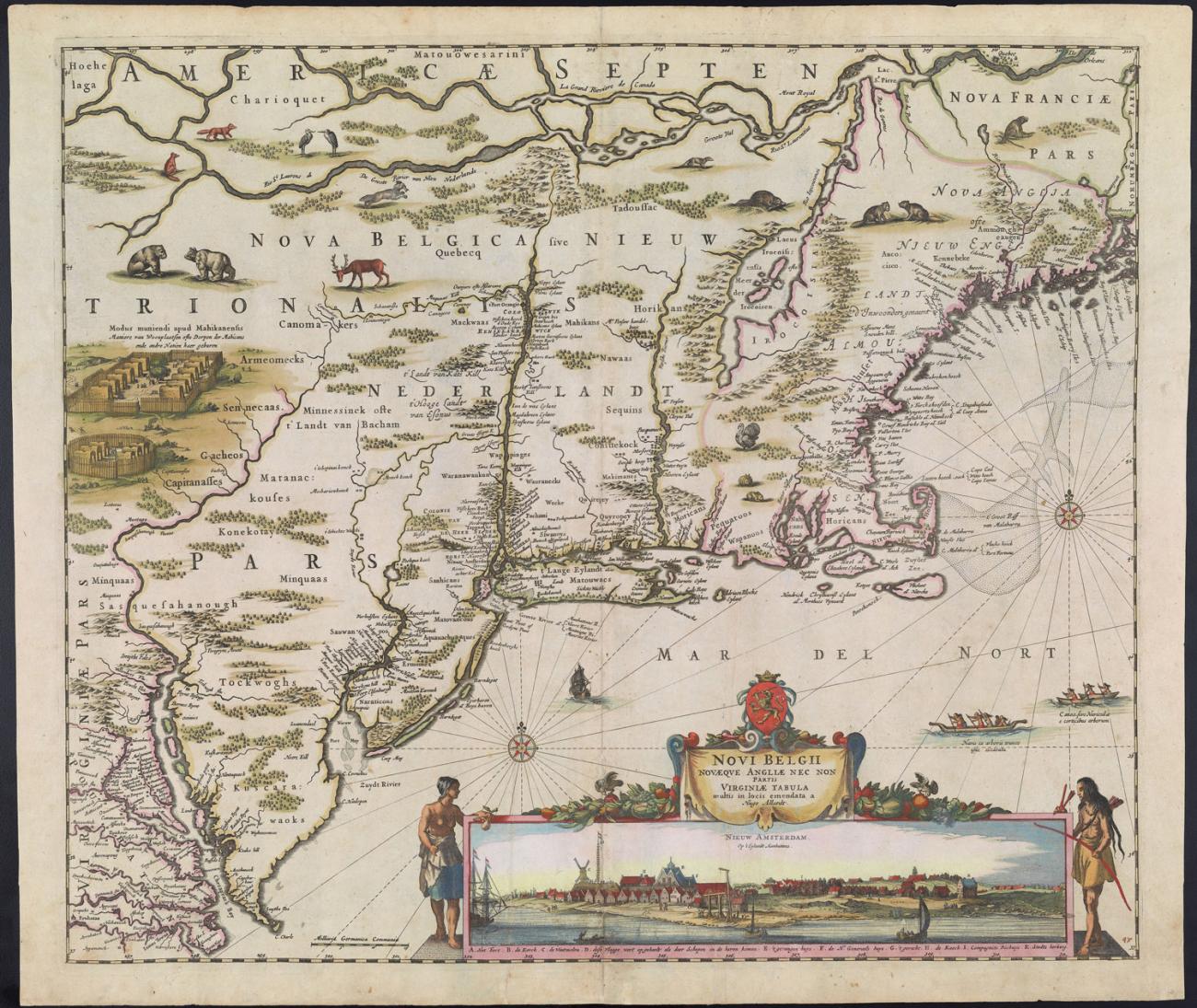

Novi Belgii Novaeque Angliae nec non partis Virginiae Tabula multis in locis emendata a Hugo Allardt, 1662. Osher Map Collection, University of Southern Maine

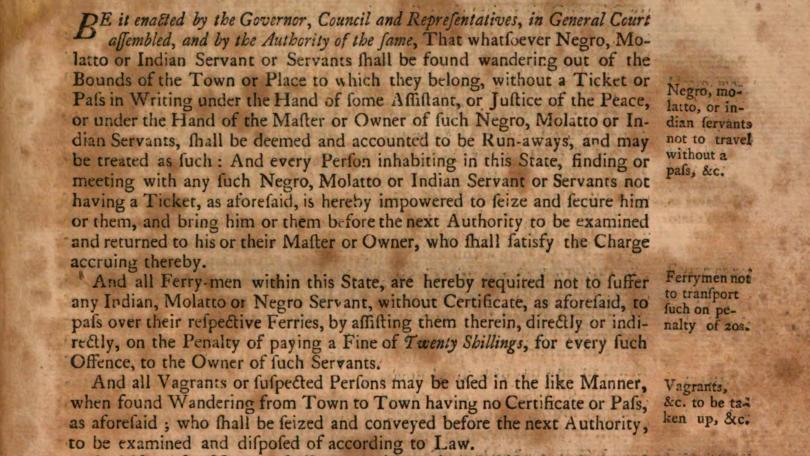

“An Act concerning Indian, Molatto, Negro Servants and Slaves." Colony of Connecticut, May, 1708

It was customary for enslaved people in New England to live in the same household as their enslavers.6 This may have fostered closer overall relationships than was often seen on Southern plantations, but it did not mean their lives were any easier. In addition to their being forced to labor, and living under the constant threat of having their families separated, enslaved people were forbidden to be on the streets after 9 p.m., and could not be outside town limits without a pass from their enslavers. In 1708, the colony passed a law imposing a minimum of 30 lashes on any Black person who disturbed the peace or attempted to strike a White person. A law passed in 1730 made it illegal for any Black, Indian, or mixed-race slave to defame the character of a White person, and made such an offense punishable by 40 lashes. This in turn made it impossible for enslaved people to safely report abuse, rendering them subject to the whims of their enslavers, not to mention the same laws as free Whites.7

In 1784, the state of Connecticut introduced a gradual emancipation scheme whereby those born enslaved in and after 1784 would be freed at age 25, for men, and 21 for women, though their mothers, fathers and all other adults remained enslaved.8 Connecticut legally ended slavery in 1848.

Notes

1. W. A. Warren, "The cause of Her grief: The rape of a slave in early New England,” Journal of American History, 93.4 (March 2007): 1032.

2. Lorenzo J. Greene, The Negro in Colonial New England, 1620-1776 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1942), 74.

3. Kathryn L. MacKay, Statistics on Slavery. Accessed May 15, 2023.

4. Joanne Pope Melish, Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and “Race” in New England, 1780–1860 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997), 17.

5. Greene, 74-75.

6. Gloria McCahon Whiting, “Power, Patriarchy, and Provision: African Families Negotiate Gender and Slavery in New England,” Journal of American History 103.3 (Dec 2016): 585.

7. Greene, 128-129.

8. “Gradual Emancipation Reflected the Struggle of Some to Envision Black Freedom,” Connecticut History. Accessed April 17, 2023.