Like that of the nation, the founding and history of Dartmouth College is inextricably linked to the ideologies and practices of settler colonialism. The aim of settler colonialism is to replace the original population of a colonized territory—along with that population’s beliefs and practices—with the settler society. This is accomplished through a variety of means, including violent depopulation, or even genocide, of the Indigenous inhabitants; the forced assimilation to colonial frameworks; and the eradication of Indigenous knowledge, cultures, and languages. Unsurprisingly, settler colonialism is often accompanied by capitalist enterprise, which results in the appropriation of resources and the enslavement of peoples who are viewed as lesser by the colonizing society in order to further exploit natural resources and produce goods at low cost.1

It is estimated that as much as 74% of the Indigenous population in what is now referred to as the Americas was wiped out by settler colonization between 1492 and 1800.2 Violence on the part of the colonizers took a deadly toll, as did diseases—including smallpox, measles and influenza, all new to the Indigenous population—that had their own devastating effect.3

In New England, European explorers enslaved Indigenous peoples even before the first settlers arrived, selling some to plantations in the West Indies. The practice continued even after a law against their enslavement was passed in 1700.4 Those who survived and were not enslaved by no means escaped, facing physical subjugation, the seizure of lands, and forced assimilation. Over time, Indigenous peoples were banned from speaking their languages or practicing their cultural traditions, religions and rituals. In some cases, children were removed from their families and sent to boarding schools in an attempt to separate them permanently from their cultures.

Iroquois Wampum Belt, 17th Century, in the collections of the British Museum

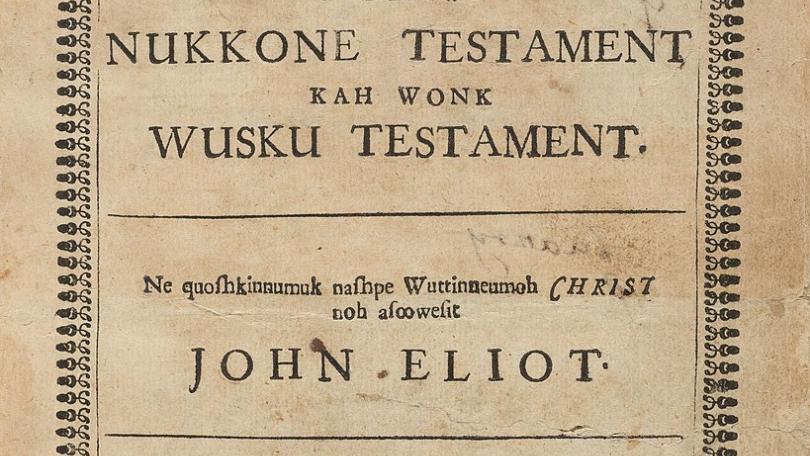

Mamusse Wunneetupanatamwe Up-Biblum God, Cambridge, 1663

As soon as they arrived in New England, colonizing settlers employed Christian conversion of the Indigenous population as a means of coerced assimilation. This practice is graphically symbolized by the Bible that John Eliot, pastor at the First Church of Roxbury in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, had printed in the language of the Wampanoag. (The Wampanoag once inhabited all of southeastern Massachusetts and eastern Rhode Island, and was the nation that made first contact with European colonizers in 1620.)

Eliot’s text allowed ministers to preach to the Indigenous tribes settled in what were known as the Indian praying towns, settlements not dissimilar to reservations. Established by English colonial governments from 1646 to 1675, these towns were part of an attempt to convert local Indigenous peoples, particularly the Wampanoag, to Christianity. Eliot’s efforts were a precursor to the work that Eleazar Wheelock would take up with Samson Occom and, later, with Moor's Indian Charity School.5

Notes

1. Kashyap, Monika Batra. “U.S. Settler Colonialism, White Supremacy, and the Racially Disparate Impacts of Covid-19” California Law Review, 23 Nov. 2020.

2. Colin G. Calloway, First Peoples: A Documentary Survey of American Indian History, Fifth Edition (Boston, New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016), 79.

3. Calloway, First Peoples, 77

4. Margaret Ellen Newell, Brethren by Nature : New England Indians, Colonists, and the Origins of American Slavery (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2015), 17.

5. Richard W. Cogley, “John Eliot and the Origins of the American Indians,” Early American Literature Vol. 21, No. 3 (Winter 1986/1987), 213-214.