Chloe, an enslaved person, was sold to Eleazar Wheelock by Ann Morison in 1762

BIOGRAPHY

On May 13, 1762, a family of three enslaved persons was sold to Eleazar Wheelock by a Colony of Connecticut widow named Ann Morison. The family consisted of a three-year-old son named Hercules, his mother Chloe, and his father Exeter. As Morison’s late husband owned an interest in two vessels involved in the transatlantic slave trade, it is likely that Exeter and/or Chloe were imported directly from the African continent. All three members of the family were named according to the conventions of the time, Hercules and Chloe in keeping with the classical and classicizing references popular in 18th-century Britain, and Exeter in line with the common practice of naming enslaved persons after places in Britain.

As recorded in the bill of sale, Wheelock paid £75 for the family, with a stipulation that £5 would be rebated if Chloe, about 35 years old at the time, should experience a return of her “rheumatic difficulty” and be rendered “disabled from business.” Chloe’s daughter, Elizabeth, remained with the widow; she would be freed on her 18th birthday only to be enslaved once more shortly afterwards. Another daughter, described in a 1765 recommendation as “very lively,” was born to Chloe shortly after her enslavement by Wheelock.

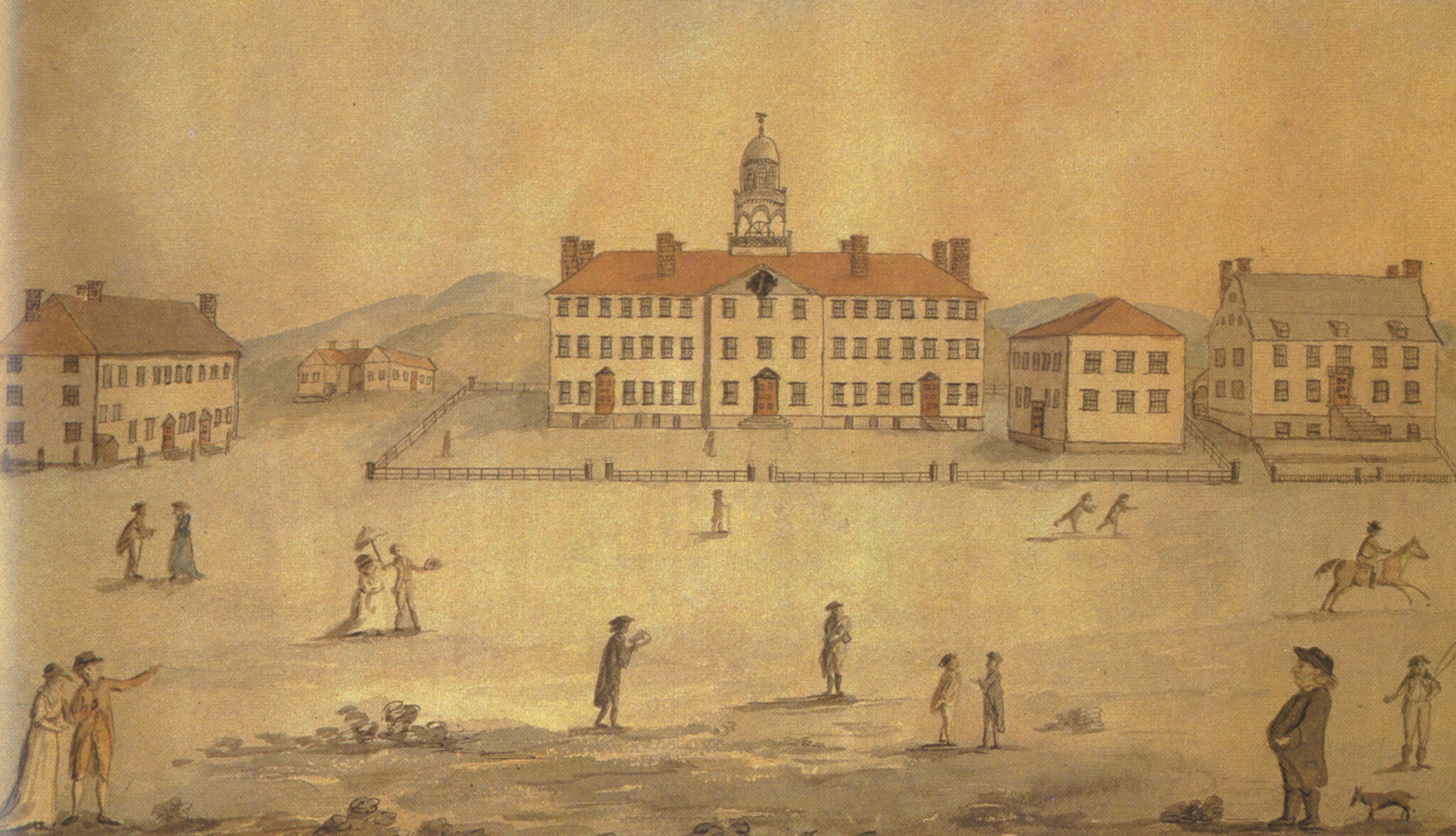

Chloe remained enslaved by Wheelock throughout the latter’s life, laboring first at one of Wheelock’s Connecticut properties, then, after 1770, in Hanover, in the Province of New Hampshire. In the 1765 recommendation, Chloe is praised as “good tempered” with an admirable understanding of “women’s business,” which could mean anything from cooking and cleaning to sewing and midwifery. The exact type of work that Chloe performed is unknown, but it likely entailed much of the immense amount of labor involved in running a household.

On February 18, 1768, Wheelock recorded Chloe’s profession of faith. As a New Light minister, Wheelock truly believed that he was saving souls by Christianizing indigenous and enslaved persons, and it is certainly possible that Chloe’s profession may simply testify to her conversion and belief—yet other factors could have been in play. It could be that Chloe became a devout believer, but it is also possible she hoped to appease Wheelock by converting and, in so doing, gain some agency for herself. On the other hand, Wheelock’s interest in christianizing Chloe can also be seen as a form of control. By imbuing his enslaved people with the fear of God, Wheelock was able to pose the threat of damnation as a way to regulate and control behavior.

Chloe and Exeter remained together at least until the end of Wheelock’s life, though not always harmoniously. In December of 1768, Exeter was brought before a justice of the peace on charges of letting his temper rage, and abusing Chloe to the point that he was becoming troublesome to “His Majesty’s good people.” (What’s not mentioned is the trouble experienced by Chloe from this abuse.) Nor is Chloe among the members of her family freed by Wheelock in his 1779 will, made less than a month before his death. The document, formally recognizing Exeter and Chloe’s marriage, makes use of fairly common legal language for the time, and leaves Exeter, “the use of Chloe his wife so long and far as he shall have occasion for her service she behaving herself well, after which she to be disposed of by my heirs.”

The next probable reference to Chloe occurs many years later. A warrant dated July 24, 1786, calls for a search of the residence of Andrew Boyton of Hanover at the request of “Chloe, a Black woman.” The document, issued after Chloe accuses Boyton of stealing a shirt from her, appears to confirm that Chloe was still alive and living in Hanover and, because she is not referred to as a servant, indicates that she had been freed by this time, possibly at the death of Wheelock’s wife, Mary, in 1784.1

Her freedom is confirmed by a letter, dated 1797, that contains the last known reference to Chloe. The subject of the document is Chloe’s daughter, Elizabeth, and her efforts to have herself declared free. Within it is a reference to a woman named “Chloe Exeter, living at Dartmouth in New Hampshire.” The letter notes: “The woman [Elizabeth] is now 51 years of age. She has Mother who is free & by whom it is beyond doubt, the fact of her being free can be established.” This statement would indicate that Chloe was still alive some 20 years after Wheelock's death; she would have been about 70 years old at the time.

Notes

1. Warrant, Mss-786424, Rauner Special Collections Library, Hanover, NH.