The life stories of enslaved people in New England are extremely difficult to recount. Little documentation survives, and that which does rarely alludes to topics other than an enslaved person’s monetary value, the conditions of their purchase and/or sale, or the work they did during their lifetimes. All that remains regarding the people enslaved by Eleazar Wheelock includes deeds, an account book, wills, correspondence, arrest warrants and a confession of faith. The pictures pieced together from these scraps of narrative are sketchy at best.

In contrast to their counterparts on plantations in the South, most people enslaved in New England lived in the same houses as, and labored alongside, their enslavers. This meant that, for better or worse, there were frequent and extended direct interactions, not only with enslavers, but with White indentured servants.1

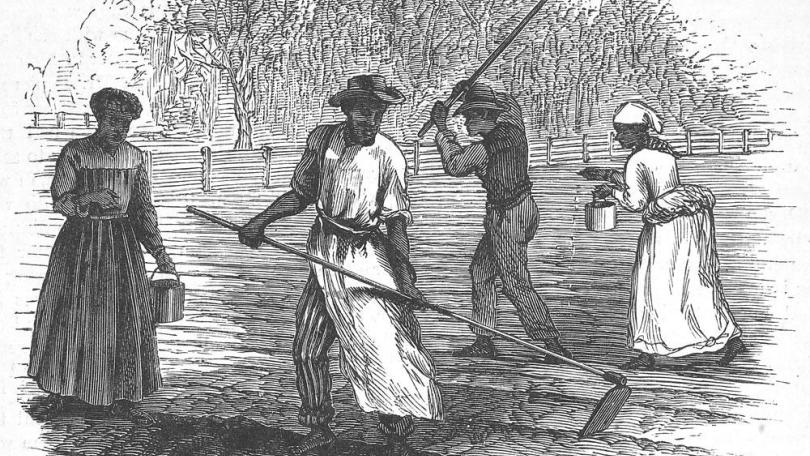

It was common for enslaved people to play multiple roles in the household. A man named Brister, for example, is noted in a letter as waiting on Wheelock. Another, Fortune, was acquired as “a man servant,” but seems to have spent a lot of time doing farm work. The men enslaved by Wheelock appear to have been mostly involved in field labor and animal husbandry. Their specific talents are noted in deeds of sale, and letters: one enslaved man is described as “prety Good with an ax how sithe & sickle,” and “handy to mend a Cart or plow.”

"Hoeing and Planting Cotton Seeds, South Carolina" from Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly, 1880

Frank Henry Shapleigh, "Old Kitchen in Bartlett, New Hampshire," 1891. Courtesy of the Hood Museum of Art

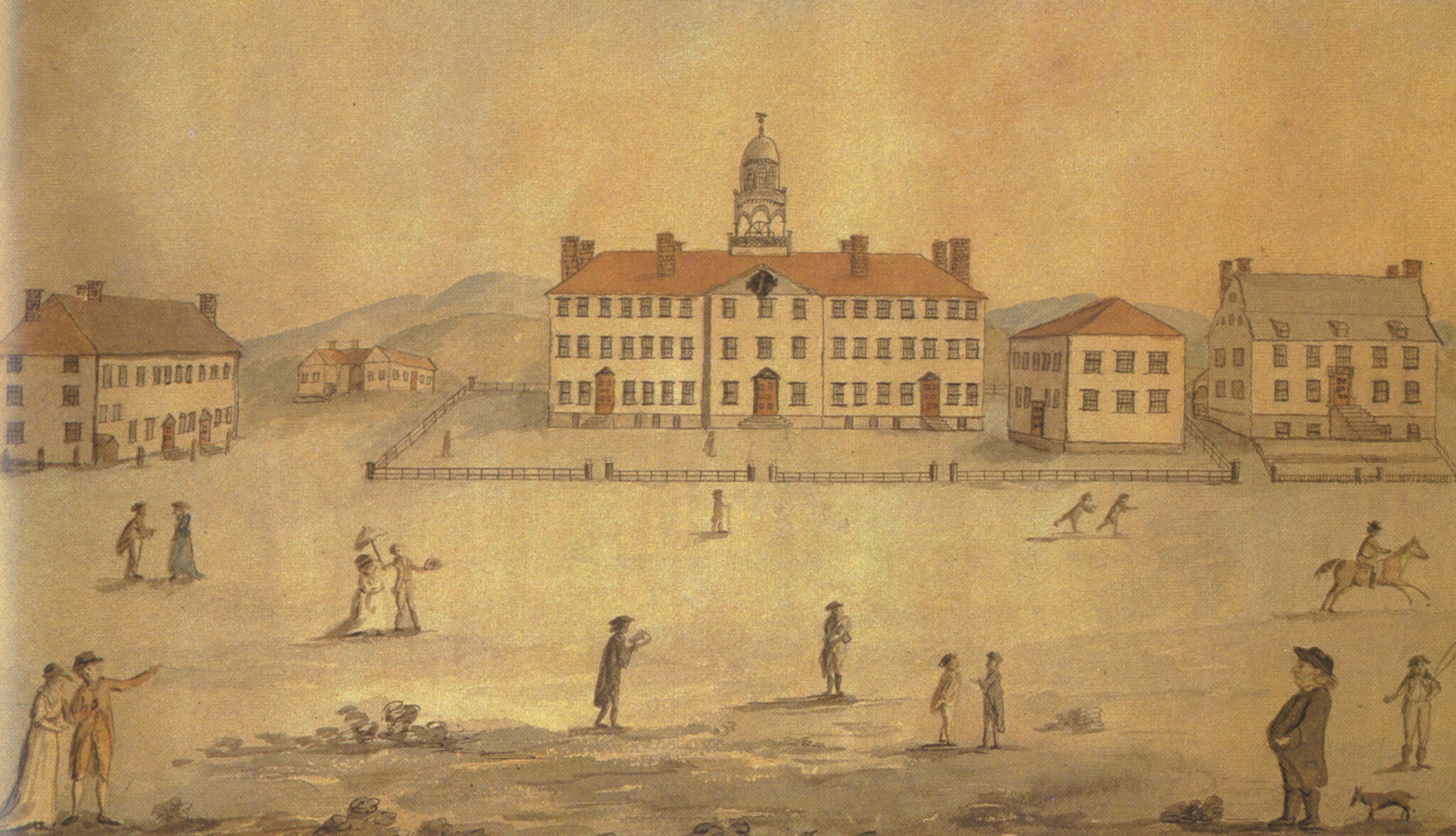

The enslaved people who journeyed with Wheelock to New Hampshire—in contrast to those who remained on his Connecticut farms in established communities—also had to endure the challenges of frontier settlement. In Hanover, they likely assisted in clearing the forest of pines, hewing rough logs for Wheelock’s first lodging, and digging wells. A man named Nando, who remained in Connecticut, worked with horses, while another named Caesar is mentioned as being able to use a canoe, a key mode of transport for Hanover’s riverside location. Wheelock also lent enslaved people to family members and rented them to neighbors—at one point, the Mohegan minister Samson Occom asked to borrow an enslaved man and a team of oxen from Wheelock to plow his field.

The work of the women enslaved by Wheelock is even less well documented, but like their male counterparts, enslaved women were likely required to perform multiple duties, perhaps working as a maid in the morning and a cook during the day, all while caring for their enslaver’s children. In a letter of recommendation allowing an enslaved man named Exeter to seek a new master, his wife Chloe is described as understanding "women’s business," which is a broad statement that could cover a wide variety of duties.

The Wheelock household at that time would have included not only himself, his wife and at least four children between the ages of six and 14, but also the students in the Indian charity school (later named Moor’s Indian Charity School) that Wheelock ran, and other enslaved and indentured people. The labor to maintain such a household would have been tremendous, including but not limited to tending the fire used for cooking and warmth, hauling water, housekeeping, childcare, gardening, food preservation, meal preparation, tending to livestock, spinning, carding, sewing and laundry.2

Beyond the labor that enslaved people provided, there are only traces of the stuff of their lives. We know from a profession of faith, and a contemporary account in a journal kept by William Dewey, a resident of Hanover, that both Chloe and Exeter converted to Christianity. We know from letters written to Wheelock that both Nando and Exeter refused to move to Hanover without certain other enslaved people, proving the existence not only of strong familial ties, but of some agency in maintaining them. We also know that Wheelock provided Exeter and Chloe’s son Hercules (also referred to as Archelaus) with an education, and raised him as a Christian.

Christianizing and bringing enslaved people into the Church was an accepted practice in New England, but providing an education was not.3 It is possible that Wheelock’s motivation for educating Hercules was more self-serving than egalitarian—a Connecticut law required owners to care for the old or incapacitated among their enslaved peoples, and Wheelock states in the letter of recommendation for Exeter that he is preparing Hercules to to care for his parents in their old age.4

In addition to providing forced labor, and having to live by the rules of their enslavers, the enslaved also had to contend with other restrictions on their lives and movement. As in the South, enslaved individuals as well as free Blacks in New England were subject to restrictive laws that governed their behavior, such as not speaking out against a White person, or not traveling outside of town limits without a pass.5 Nevertheless, both Hercules and Brister, according to an arrest warrant for Caesar, are said to have had sexual relations with a White servant girl. Additionally, these laws did not prevent Chloe from filing a complaint against Andrew Boynton of Hanover for stealing a shirt from her.6

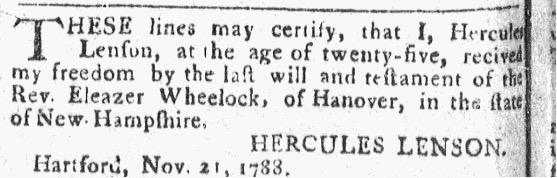

At the end of his life, Wheelock left landholdings to several of the enslaved men in his will, albeit with paternal stipulations related to their behavior and moral standing. It is interesting to note that none of them appear to have taken him up on this offer. While Brister remained in Hanover, we do not know where he resided. Hercules, on the other hand, appears to have taken the last name of Lenson and moved back to Connecticut, where he placed an ad in a Hartford newspaper declaring his freedom.7

Hercules Lenson, advertisement in Connecticut Courant, 1788

Notes

1. Lorenzo J. Greene, The Negro in Colonial New England, 1620-1776 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1942), 222-223.

2. Leon B. Richardson, History of Dartmouth College (Hanover: Dartmouth College Publications, 1932), 19.

3. John Saillant, “Slavery and Divine Providence in New England Calvinism: The New Divinity and a Black Protest, 1775-1805,” New England Quarterly 68.4 (Dec. 1995): 584.

4. Greene, 138.

5. Greene, 124-138.

6. Grafton County, N.H. Justice of the Peace, Warrant, Mss 786424, Rauner Special Collections Library, Dartmouth College.

7. Hercules Lenson, Advertisement, The Connecticut Courant, December 1, 1788.