Letters and other documents that cast light on Dartmouth College founder Eleazar Wheelock's ownership of enslaved persons, and Dartmouth College's early involvement in the institution of slavery.

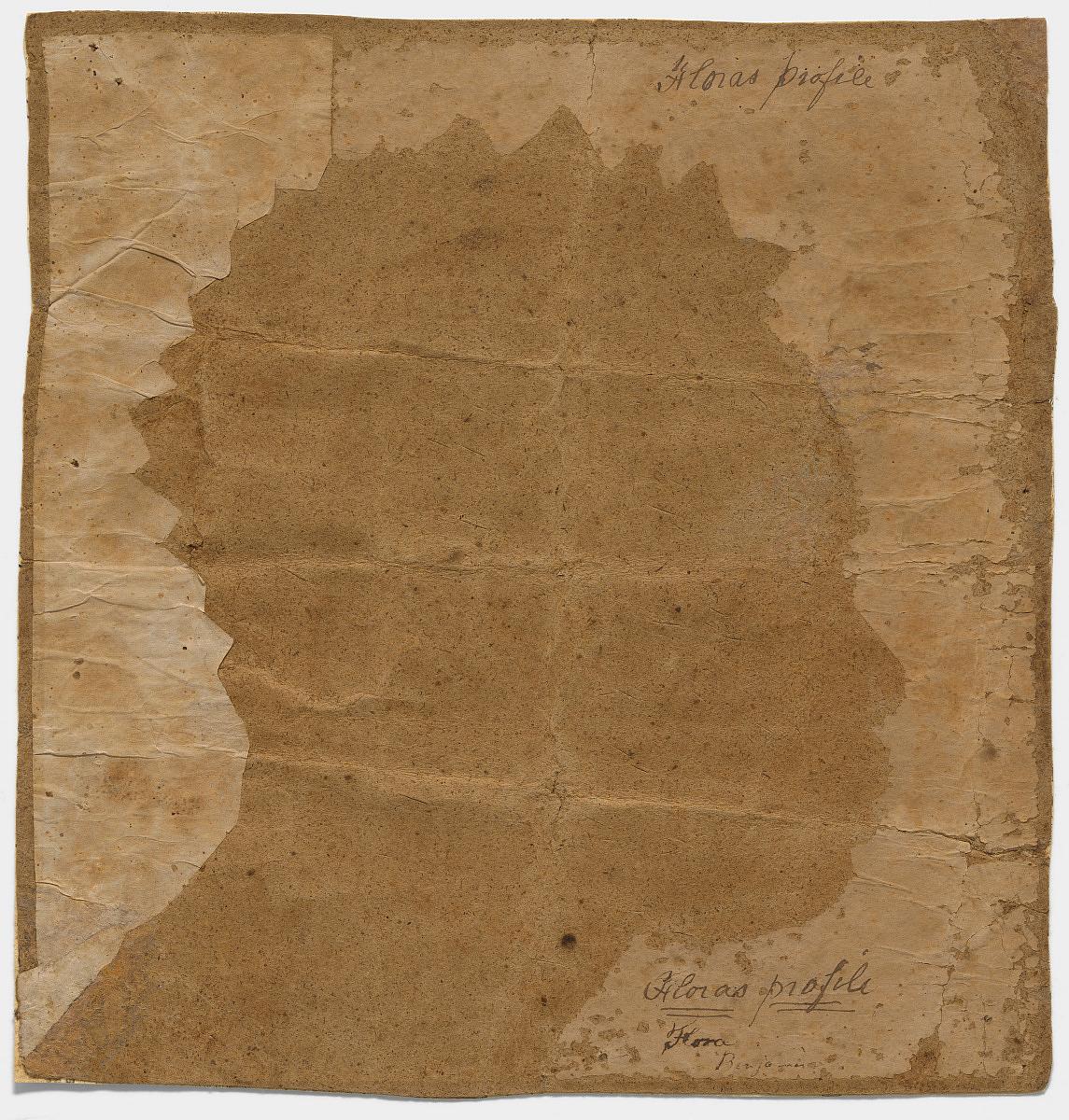

Hand-cut silhouette of Flora (ca. 1777 - 1815), a woman enslaved in Connecticut. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture and National Portrait Gallery, Museum purchase through the American Women’s History Initiative Acquisitions Pool, administered by the Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative

Wheelock, Dartmouth, and the Role of Slavery

Introduction by Peter Carini, College Archivist, and Deborah King, Associate Professor of Sociology

Scope of the Project

Enslavement Documents from the Wheelock Collection includes digital images and transcriptions of all identified records in the Eleazar Wheelock Collection at the Dartmouth Library that reference enslaved people or Black people with whom Wheelock interacted. The documents include items such as deeds of sale, warranties, letters, a confession of faith, wills, and accounts. In addition to documenting the persons enslaved by Wheelock, the documents also include references to one White indentured servant, several free Black people, as well as other enslaved people residing in areas of Connecticut and New Hampshire where Wheelock lived. For example, there are a series of depositions related to a case where an enslaved woman accused a man, likely a member of Wheelock’s congregation, of impregnating her.

Note: Eighteenth-century references to Black enslaved and free people utilized the now archaic and offensive term "negro."

Slavery in New England

New England played a crucial, if often overlooked, role in the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Its trees provided the timber and masts for British ships that departed its seaports transporting the provisions from its waters and fields to sustain distant plantations. These ships returned laden with the enslaved and with the slave-produced cotton bales and bags of sugar that New England’s mills wove into cloth and distilled into rum.

While Enslavement Documents from the Wheelock Collection focuses on the enslavement of Black people, it is important to note that Indigenous people were enslaved by European explorers as early as 1605, and continued to be the predominant enslaved people in New England into the 18th century, even after a law against their enslavement was passed in 1700.1 The enslavement of Black people in the New England colonies has been traced back to as early as 1638.2 The population of Blacks, enslaved and free, between 1771 and 1776 was estimated at 16,034 or 2.4 percent of the total population.3 By contrast, enslaved Black people made up 37.9 percent of the population in southern colonies in 1750.4 Regardless the numerical representation, slaves were also an important status symbol. Most of New England’s clergymen, lawyers, and merchants owned at least one enslaved African or Indian person. Although Connecticut, where Wheelock lived prior to 1770, lacked a major shipping port, it was then the primary slave-holding colony in New England. This is likely due to its greater arable acreage that would have required significant labor, beyond that of free laborers or indentured servants, and to its concentration of wealth at the time.5

Wheelock’s Background

Eleazar Wheelock (1711-1779) was a minister by occupation. His pastoral position at the Congregational church in Lebanon Crank, Connecticut, came with 20 acres of land along with his salary.6 By 1763, his holding had grown to approximately 158 acres.7 Later he expanded these holdings to include additional acreage. In 1748, his father died and left him a 300-acre farm in Windham, Connecticut. The arrangement for his father’s farm is unclear, but it appears that he either leased the farm, or hired someone to manage it for him. However, he cultivated the immediate acreage in Lebanon himself, with those he enslaved. At one point Wheelock’s land holdings were estimated to be worth between £2,000 and £3,000, which even in colonial pounds would have been a significant sum for a minister at the time.8

Over the years, various scholars and historians have reported Wheelock’s slave holdings as ranging from four to 12 enslaved people.9 The documentation presented here places this number closer to 18 enslaved people over his lifetime, although the inconsistent use of names for enslaved people makes it difficult to determine an exact number.

The Enslaved

The first mention of an enslaved person in Wheelock's household appears in 1735. Between 1743 and 1769, there are references in these documents to the purchase of eight enslaved people, six men and two women. Nine additional enslaved people appear in other documents including letters, warrants, accounts, and wills. In all, the records here represent 18 individuals enslaved by Eleazar Wheelock. However, it is likely that Wheelock owned even more enslaved persons. One reason we believe this is a 1761 deed of sale in which Wheelock is buying a man named Sippy back from two men to whom he had earlier sold Sippy, so that they could pay off their other debts. This means that Wheelock must have purchased Sippy prior to the 1761 transaction, but we can find no other record of his existence, either before or after this document was signed. Likewise, the enslaved men named Billy and Elijah only appear in Wheelock’s account book and nowhere else in the extant record. In other words, it is entirely possible for Wheelock to have enslaved others without any documentation existing to reveal those people or their enslavement.

In addition to those enslaved by Wheelock, several other individuals enslaved by others, and two free Black people are also represented in the documents.

The Role of the Enslaved in the Founding of Dartmouth College

While we know few specifics about the work performed by individuals that Wheelock enslaved, we can make some suppositions based on comments in the documents and general knowledge of enslavement in New England at the time. For instance, it is known that most enslaved people in New England performed a variety of tasks. Unlike those enslaved on large southern plantations, an enslaved person might perform field work or a skilled trade during the day and act as a servant during other times. From Wheelock’s records, we know that Fortune and Billy performed a variety of field work, even though Fortune is also referred to as a “man servant” in a deed of sale. Exeter is described as skilled in all manner of husbandry. Chloe, who appears to be Exeter’s wife, and Dinah are engaged in various domestic tasks, from cooking and cleaning, to carding, spinning, and even assisting with childbirth.

It appears that seven or eight of those enslaved persons accompanied Wheelock and later his family to Hanover, where one or more of the men drove the carriage and probably fed, shoed, and groomed the horses. Other than a reference to Caesar residing in the kitchens at Dartmouth College, and a search for a negro cook, there are no details regarding the tasks they performed. We can suppose, based on past references, that their labor supported the institution by helping to cut down trees, clear land, erect and clean college buildings, dig wells, plow and haul with oxen, sow, plant and harvest. In addition, they likely assisted with cleaning, washing, mending, spinning, cooking, and nursing, either for the Wheelock household, or for the tutors and students.

This digital collection is in progress, and will eventually include Wheelock's will and other related materials. The original documents in this collection are housed in Rauner Special Collections Library as part of the Eleazar Wheelock Collection, MS-1310.

1Newell, Margaret Ellen. "Indian Slavery in New England." Indian Slavery in Colonial America. Ed. Alan Galay. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2009, 35.

2Warren, Wendy. New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early America. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2016, 9.

3Greene, Lorenzo J. The Negro in Colonial New England, 1620-1776. New York: Columbia University Press; P. S. King Staples, ltd., 1942, 74.

4Colonies consisted of Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. Table Series Z 1-19, Estimated Population of American Colonies: 1610-1798, in Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970, Part 2. Washington, D. C.: Bureau of the Census, U. S. Department of Commerce, 1975, 1168.

5Greene, 74-75.

6The North Society in Lebanon. Action calling Wheelock to be their minister, etc., Mss 735174, Rauner Special Collections Library, Dartmouth College.

7Note card 14, Deeds Indicating Real Estate Transfers in Lebanon, Leon B. Richardson papers, MS-505, box 1, folder 2, Rauner Special Collections Library, Dartmouth College.

8Richardson, Leon B. History of Dartmouth College. Hanover, N.H: Dartmouth College Publications, 1932, 19.

9Wilder, Craig Steven. Ebony & Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2013, 113-114, 123, 126-128, 135, 146.

Project Credits

- Peter Carini and Jennifer Mullins were the project managers

- Peter Carini researched and selected the materials

- Deborah King provided historical consultation

- Conservation by Lizzie Curran

- Digitization by Ryland Ianelli

- Transcription by Peter Carini, Betty Kim ‘20, Julia Levine ’23, and Julia Logan

- Encoding in TEI by Laura Braunstein, Jeremy Mikecz, and Elizabeth Hadley '23

- Encoding review by Elizabeth Hadley '23 and Elizabeth Shand