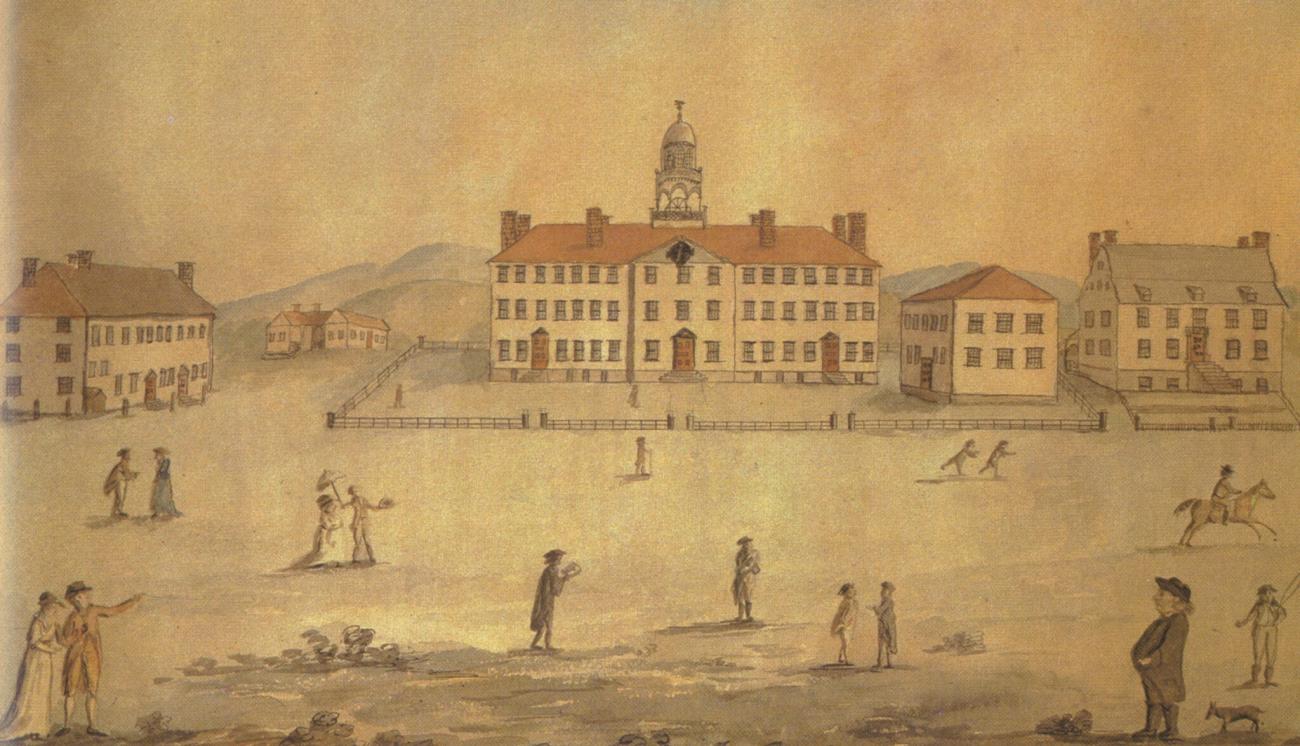

Exeter, an enslaved person, was sold to Eleazar Wheelock by Ann Morison in 1762

BIOGRAPHY

On May 13, 1762, a family of three enslaved persons was sold for £75 to Eleazar Wheelock by a Colony of Connecticut widow named Ann Morison. The family consisted of a son named Hercules, his mother Chloe, and his father Exeter. As Morison’s late husband owned an interest in two vessels involved in the transatlantic slave trade, it is likely that Exeter and/or Chloe were imported directly from the African continent. What is not clear from the deed of sale, is that Morison also owned Exeter’s daughter, a girl named Flora, who remained enslaved to Morison and later to her heirs. All three members of the family were named according to the conventions of the time, Hercules and Chloe in keeping with the classical and classicizing references popular in 18th-century Britain, and Exeter in line with the common practice of naming enslaved persons after places in Britain. Their ages at the time are listed as three, 35 and 48, respectively.

Exeter appears to have had some small agency over the course of his and his family’s life, yet despite a 1765 recommendation allowing him to exercise that agency by seeking a new master, the family remained with Wheelock throughout the latter’s life. Exeter’s eventual freedom was ratified by Wheelock’s 1779 will, made shortly before Wheelock died. Chloe and Archelaus (Hercules, renamed) remained enslaved. In fact, Wheelock, making use of fairly common legal language of the time, leaves Exeter “the use of Chloe his wife so long and far as he shall have occasion for her service she behaving herself well, after which she to be disposed of by my heirs.”

If the 1765 recommendation praises Exeter, it is only to a point, and the fact that Exeter was permitted to seek a new situation at all points to possible dissatisfaction on both sides. Exeter, who appears to have been primarily put to the enormous amounts of manual labor that both farming, breeding and raising stock, then establishing the Dartmouth campus entailed, was said by Wheelock to be “honest, manly, kind, neighborly,” and “as good a man for business…as any man I ever employed.” Then comes the caveat that Exeter is also subject to a violent temper and that when he is “in his passions” he will “lie and sometimes swear.”

And, indeed, become violent. In December of 1768, Exeter was brought before a justice of the peace on charges of letting his temper rage, and abusing Chloe to the point that he was becoming troublesome to “His Majesty’s good people.” Two years later, after Wheelock moved from Connecticut to Hanover, in the Province of New Hampshire, to found Dartmouth College, a letter from Wheelock’s nephew declares that Exeter, still in Connecticut with his family, is being “very hys in the insteph” by refusing to leave without Peggy (that Peggy is the daughter of Chloe and Exeter, born shortly after their enslavement by Wheelock, is uncertain though likely, and it’s possible that, after being forced to leave behind Flora when the family was sold to Wheelock, Exeter is putting his foot down about Peggy). Exeter may have been allowed a certain amount of control over his destiny, but he is still seen as acting above his station when he protests a painful separation; and Exeter and his family did eventually make the move to Hanover with Wheelock’s wife, Mary, in 1770.

In the early 19th century, William Dewey, a local farmer who recorded the deaths and sundry events of the region where Dartmouth resides, wrote that Exeter was pious and well-respected in the village. He also noted that “Upon his face were several spots of a Copper color of more than an inch in diameter,” a physical trait of unknown origin. It is Dewey’s diary that records Exeter’s age as 75 at the time of his death, but the record is not authoritative in this regard, and Exeter’s fate beyond these notes is unknown.