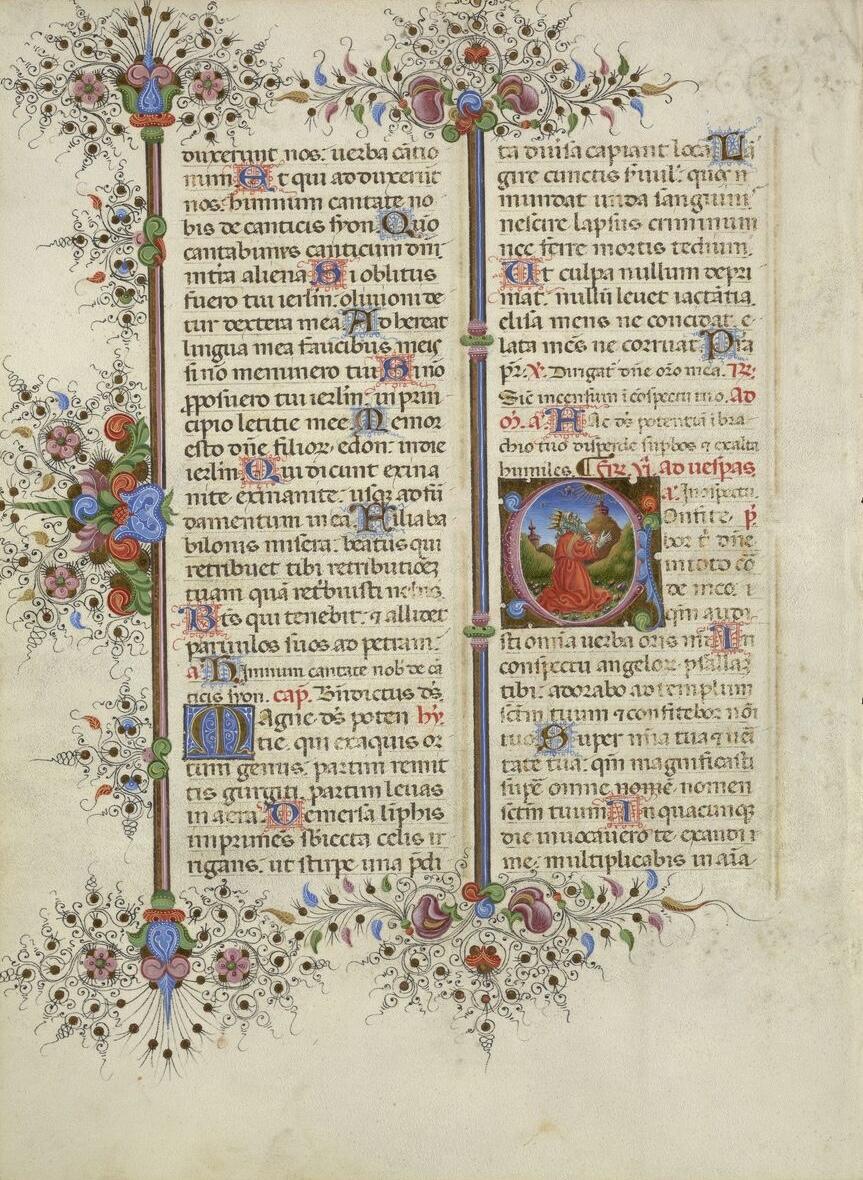

From a series of 13 single leaves of the Llangattock breviary, ca. 1470, each containing initials, miniatures, and floral borders. See Manuscript Codex 002074, Rauner Special Collections Library, Dartmouth.

This digital collection brings together 161 manuscript fragments housed in Rauner Special Collections Library. The majority of these fragments were originally produced in pre-1600 Europe. However, twenty fragments in the collection were produced in non-Western nations and of these, ten were produced between 1700 and 1900. The majority of fragments in this digital collection are from books of hours, bibles, breviaries, antiphonaries, and graduals, but it also includes leaves from choir books, poetry collections, Korans, and more. As a whole, the digital collection presents examples of the manuscript tradition as it was practiced across cultures and over time.

Origins of the Fragments

“Fragments” is itself a slippery and elusive genre classification. Its definition has been the subject of debate in fragmentology, the field of study devoted to medieval manuscript parts. As a catchall term, manuscript fragments refer to parts of codices that are now detached from the parent codex. This description veils, however, a complex media history. Fragments fall under three main types: waste material, cuttings, and leaves. These categories reflect the three different routes by which a bound codex became dismembered. Waste fragments are a result of the recycling and reuse practices of medieval and early modern bookbinders. Since parchment was an expensive resource, binders used pieces of earlier manuscripts to reinforce bindings, or to use as pastedowns or flyleaves (see Mss 002286). Cuttings refer to portions of leaves that have been cut up for their decorative or aesthetic value — oftentimes illuminated miniatures and initials. Cuttings result from eighteenth- and nineteenth-century leisure practices, when manuscripts sold in the budding antiquarian book trade might be cut up and reassembled in scrapbooks or albums, or used to extra-illustrate printed books (see Rare Book ND2895.H36 D335 Box 1 No. 9). Lastly, single leaf fragments result from the early-twentieth century trade in rare books and manuscripts. Realizing the profit in selling hundreds of single leaves rather than a single codex, sellers began deliberately breaking up manuscripts, selling them leaf by leaf. The most notorious of these “book-breakers” was Otto Ege (1881–1951); ten leaves originally sold by Ege are digitized here. Single leaf fragments make up the bulk of this digital collection.

Digital Afterlives

This collection partakes in the ongoing relationship between digital technologies and fragmentology. Remediated in the digital realm, fragments that had once been bound together can be virtually reassembled, opening up avenues to study when and how the codex was fragmented, to better understand the contents and history of a fragment, and to investigate the relationship between sets of fragments. This digital collection originated from a collaborative digital humanities project invested in these questions, ManuscriptLink, now defunct. Published here, “Manuscript Fragments from the Ninth through the Nineteenth Centuries” contributes to the study of the origin, history, and nature of fragments, as well as their digital afterlives.

Project Credits

- Initial inventory curation: Morgan Swan

- Inventory curation and review: Elizabeth Shand and Elizabeth Hadley ‘23

- Conservation: Johanna Pinney

- Digitization: Ryland Ianelli

- Metadata Support: Shaun Akhtar