The diary of Ada Blackjack, sole survivor of the Wrangel Island expedition, March-August 1923

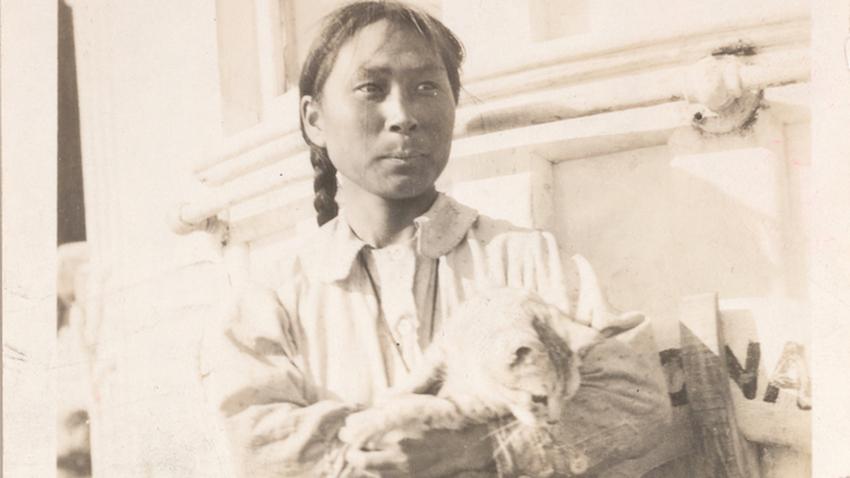

Ada Blackjack with the expedition's cat, Vic, aboard the rescue ship, 1923

Ada Delutuk Blackjack was born in 1898 in the Iñupiat village of Spruce Creek, in what was then known as the District of Alaska. Her mother sent her to Nome when she was eight years old. There, Methodist missionaries taught her to read, write, and sew. She married at sixteen, but within five years her husband had abandoned her and their surviving child, a son named Bennett. Far from home and without money, she was forced to place Bennett in an orphanage and found work as a seamstress.

In 1921, in an ill-fated attempt to settle Wrangel Island (in the Chukchi Sea north of Siberia) and establish a territorial claim, Vilhjalmur Stefansson recruited four men -- Allan Crawford, Milton Galle, Lorne Knight, and Fred Maurer -- to settle on the island and hunt game. While outfitting the expedition in Nome, the team hired Ada Blackjack, a woman whose ancestors had lived in area homelands since time immemorial. After an expected relief ship failed to appear late the following year, Crawford, Galle, and Maurer set out in January 1923 to walk over the pack ice to Siberia. They were not heard from again. Knight, suffering from scurvy, remained behind with Blackjack; he died on June 23, 1923. Left with the expedition’s cat, Vic, Blackjack survived alone until the arrival of Harold Noice and the crew of the Donaldson, on August 20, 1923.

Ada Blackjack’s diary is a testament to survival at its most basic. She records the daily needs of the body: the desperate hunt for food; Knight’s physical and psychological deterioration; the daily chores of laundry, sewing, and emptying the “slop bucket”; and the cycles of her menstrual period. She tracks her emotional state as well: her sorrow in being separated from Bennett; her pride in learning to hunt, kill game, and sew clothing to bring home to her family; and most of all, her fear and loneliness. Perhaps the most striking aspect of her story is that she began the trip with no experience or training in hunting and other survival skills that kept her alive; she started as the expedition’s seamstress and taught herself nearly everything else. Like so many Indigenous women before her, she survived both the harsh conditions of the Arctic and the separation from her son and family. According to Indigenous worldviews, she survived due to and was carried home by her deep-seated ancestral knowledge, including hunting, creating, and other essential skills.

Ada Blackjack’s diary is part of the Dartmouth Library’s collections because of her relationship to the Wrangel Island expedition commissioned by Stefansson; the diary is one set of documents among over one hundred linear feet of archival materials from sixty years of his life as a polar explorer. We are now making the diary widely accessible to readers through the digitization of materials related to the Wrangel Island expedition. But, to whom does the diary belong? Ownership of cultural property is fraught. The physical object is “owned” by the Dartmouth Library as part of the Vilhjalmur Stefansson Papers. But the diary itself is a cultural artifact that points to varied legacies. It is a diary of a remarkable Indigenous woman interacting with white settlers attempting to exert imperialist designs on northern territories. In that regard, it clearly belongs to an Indigenous culture. Simultaneously, it is a document, written in English, of western expansion and exploration that is a partial result of Ada’s own alienation from the culture of her birth, as she was educated by Christian missionaries. It exists in both of these traditions, and is independent of neither. Perhaps it “belongs” to the legacy of a specific time and space influenced by conflicting cultural perspectives. Our reappropriation of it here -- to tell a story of exploration and imperialism -- offers an opportunity to delve into that entanglement, but it will never answer the question, “to whom does this diary belong.”

Through a series of partnerships and initiatives, including the Mellon-funded Advancing Pathways for Long-term Collaboration project, the Dartmouth Library is working toward the responsible stewardship of Indigenous materials like Ada Blackjack’s diary in keeping with the Protocols for Native American Archival Materials.

The Ada Blackjack Diary digital project is part of a larger project to digitize materials related to Wrangel Island, supported by the Alaska Library Network and by a gift from the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation.