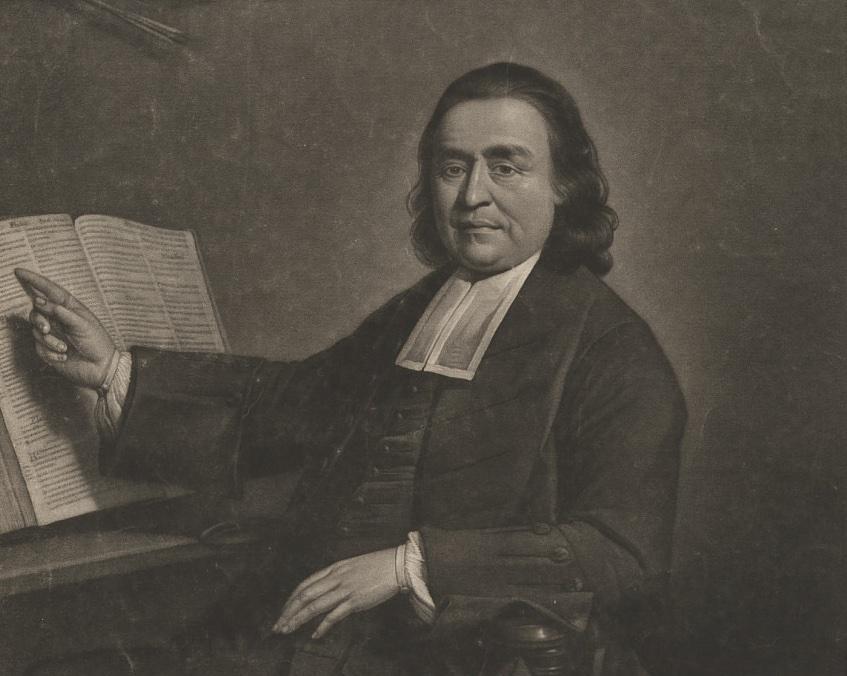

Samson Occom (Mohegan, 1723-1792), was a teacher, minister, diplomat, and public intellectual

Mezzotint of Samson Occom by Jonathan Spilsbury, after a portrait by Mason Chamberlin, 1768. National Portrait Gallery, public domain.

BIOGRAPHY

To learn more about Samson Occom, visit The Occom Circle, a digital collection of over 500 documents by and about Occom.

A teacher, minister, diplomat, and public intellectual, Samson Occom was born in 1723 at Mohegan, near present-day New London, Connecticut. By his own choosing, Occom converted to Christianity at age 18, during the Great Awakening. In 1743, he went to study with Eleazar Wheelock, a Congregational minister in Lebanon, Colony of Connecticut. Occom was an unusually gifted student, and in addition to mastering writing and religious philosophy, he achieved a reading knowledge of four languages: Greek, Hebrew, Latin and English. Following four years of study with Wheelock, he moved to Montauk on present-day Long Island where he spent 12 years as an educator and minister to the Montauk and Shinnacock communities. In 1751, he married Mary Fowler, the daughter of a prominent member of the Montauk tribe. Eight years later, in 1759, he was ordained a Presbyterian minister.

In 1763, Occom returned to Mohegan where he became a popular spiritual leader and teacher among his own people. At the same time, in a quest to bolster alliances between Mohegan and the Haudenosaunee, Occom began to travel back and forth between Mohegan and Iroqouia in what is now upstate New York. These trips allowed Occom to hone his already strong speaking skills, become versed in the art of diplomacy, and also promote Moor's Indian Charity School.

After his return to Mohegan, Occom also became involved in the Mason Land dispute, a longstanding disagreement between Mohegan and the Colony of Connecticut over the usurpation of ancestral lands. As part of this effort, Occom took the bold step of penning a letter to King George III requesting royal intervention in the case, a move that landed him in hot water with Colonial and religious authorities. In an effort to separate Occom, and himself, from the controversy, Wheelock asked Occom to travel to England to raise funds for the school.

Occom left for England in December of 1765. While there, he traveled widely and met with leading religious and political figures such as George Whitefield, Lord Dartmouth, and King George III, among others. He also preached to large audiences in England and Scotland. Ultimately, his trip created significant goodwill toward Wheelock's school among the ruling class, and raised £12,000 in support of the venture.

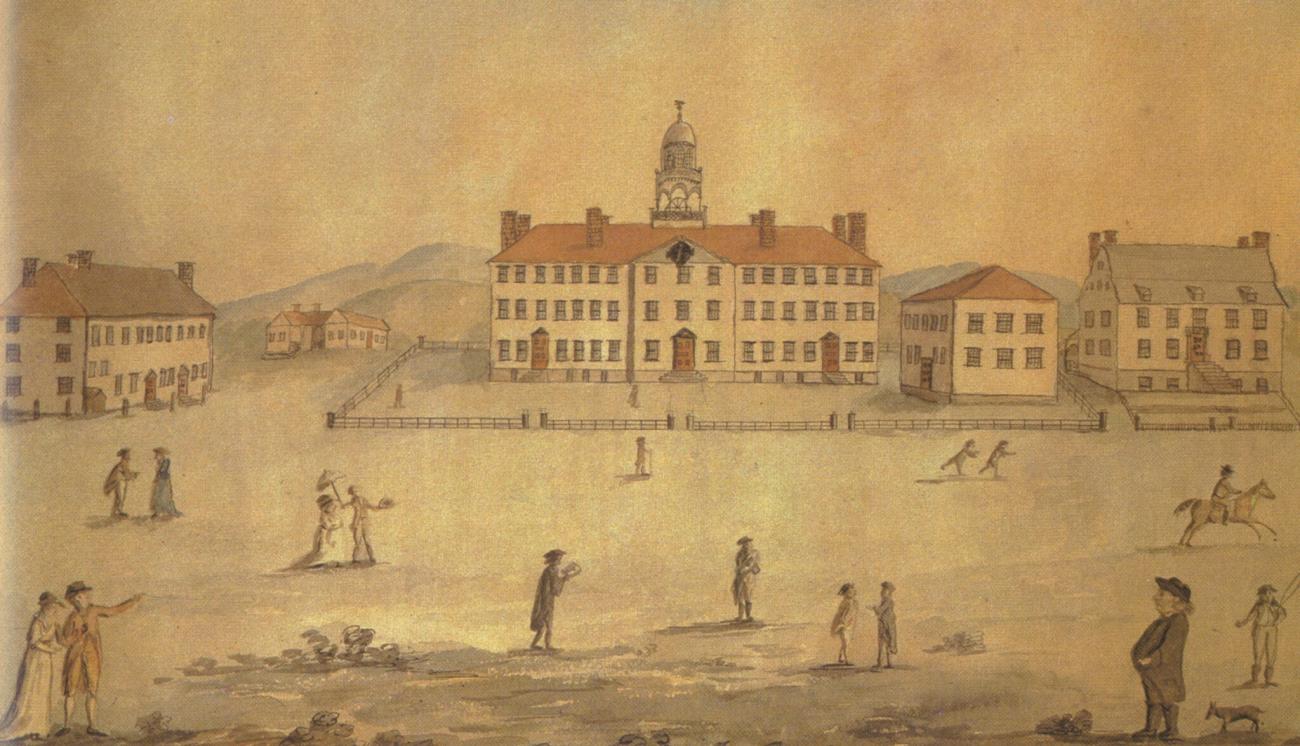

Wheelock had started Moor’s based on Occom's success on Montauk, though Wheelock's ultimate motivation was less about lifting up Indigenous people and more about assimilation through religion. In Occom's absence, Wheelock’s quest for a charter for his school, and his lack of success in applying his didactic teaching methods to Indigenous students, caused him to shift his mission from founding a school for Indigenous youth, to creating a college for Anglo-Americans. After many attempts, Wheelock obtained a royal charter for a college from John Wentworth, Governor of the Province of New Hampshire, on December 13, 1769.

Upon his return from England, Occom quickly discovered what Wheelock had done with the funds he had helped to raise. He also found that his family, whom Wheelock had promised to support in his absence, had been sorely neglected. In 1771, he wrote Wheelock a scathing letter in which he accused Wheelock of misappropriation of funds, and declared they would both be "Deem’d as Liars and Deceivers," a fate worse than death to many indigenous people. Occom and Wheelock never saw each other again, and Occom never set foot on the campus of the institution he worked so hard to found.

In 1772, Occom delivered a sermon at the execution of Moses Paul, a Wampanoag man convicted of murder. This sermon catapulted him into the limelight. The work was published, went through 19 editions, and was even reprinted in Welsh. And though prior to his departure for England, Occom wrote to Wheelock to request the use of a slave and a yoke of oxen to assist with work on his farm, he came to assume an abolitionist stance and to speak out against slavery, including a statement against the institution in a sermon of 1787.

Occom continued to advocate for his people in the Mason Land Case until it was decided against the tribe in 1773. Disillusioned by the hypocrisy of Anglo-American Christians, Occom, in conjunction with a pan-tribal group of Christian Indigenous people, founded the Brothertown community in Oneida, NY. Occom, who had become a kind of public intellectual of his day, moved to Brothertown with his family in 1789. He died there in 1792.