John Wentworth was the last royal Governor (1767 - 1775)

John Wentworth (1737-1820) was appointed Governor of the Province of New Hampshire on August 7, 1766. As the representative of King George III, he had jurisdiction over the province’s territories, waterways, natural resources, civil and criminal legal systems, and commerce.1 Wentworth’s appointment was not unrelated to his family’s political prominence and wealth. His father, Mark Hunking Wentworth (1709-1785), possessed vast landholdings, and maintained a near monopoly as the supplier of masts and provisions for the royal navy. Trade with the West Indies increased his wealth, and made him a very rich man in the Province.2

As Surveyor General of the King's Woods in North America, John Wentworth was responsible for the royal forests “from New England down to the Carolinas,” which produced timber for the construction of ships, wharves and buildings. Tall pines, so often seen in Dartmouth symbols, were necessary for the masts and booms on sailing ships, and were reserved for the royal fleet that protected the British maritime ports and trading routes, including those transporting the enslaved and the products they produced.

As it happened, Wentworth was in England to handle family business matters when Reverends Samson Occom and Nathaniel Whitaker traveled there to raise the money that Occom believed would support Eleazar Wheelock’s school for Indians. Their paths crossed, and the resulting conversations were fruitful3, as Wentworth contributed to the English Trust and promised to look for a site in New Hampshire to which the school could relocate.

In 1769, Wentworth made good on his promise, and issued a charter to Wheelock to establish a college:

"...... especially by the consideration that such a situation would be as convenient as any for carrying on the great design among the Indians; and also, considering, that without the least impediment to the said design, the same school may be enlarged and improved to promote learning among the English…."4

Crucially, Wentworth deeded 500 acres directly to Wheelock and Dartmouth, and approved the land grants that various townships and individuals offered to attract the college, estimated to total 17,000 acres.5

As detailed in the charter, the Crown and Governor viewed establishing the college in the province as pivotal for British colonial objectives. It was reasoned that giving land to prominent individuals would attract more European settlers to the largely underpopulated, western regions of the province, thus strengthening its territorial defenses against other European imperial powers (France and Spain), the indigenous resistance (e.g. the Pequot War and Wampanoag Chief Metacom’s War), and the British colony of New York.6

Among the proprietors and early settlers in the upper Connecticut River valley were previous supporters of Wheelock’s Indian academy and its professed mission of “civilizing and christianizing children of pagans.” But the Governor’s and settlers’ primary interests in establishing a college “for English youth and any others,” were meeting regional needs for trained ministers, teachers and doctors, protecting personal land rights, encouraging development through land improvements, and attracting businesses.

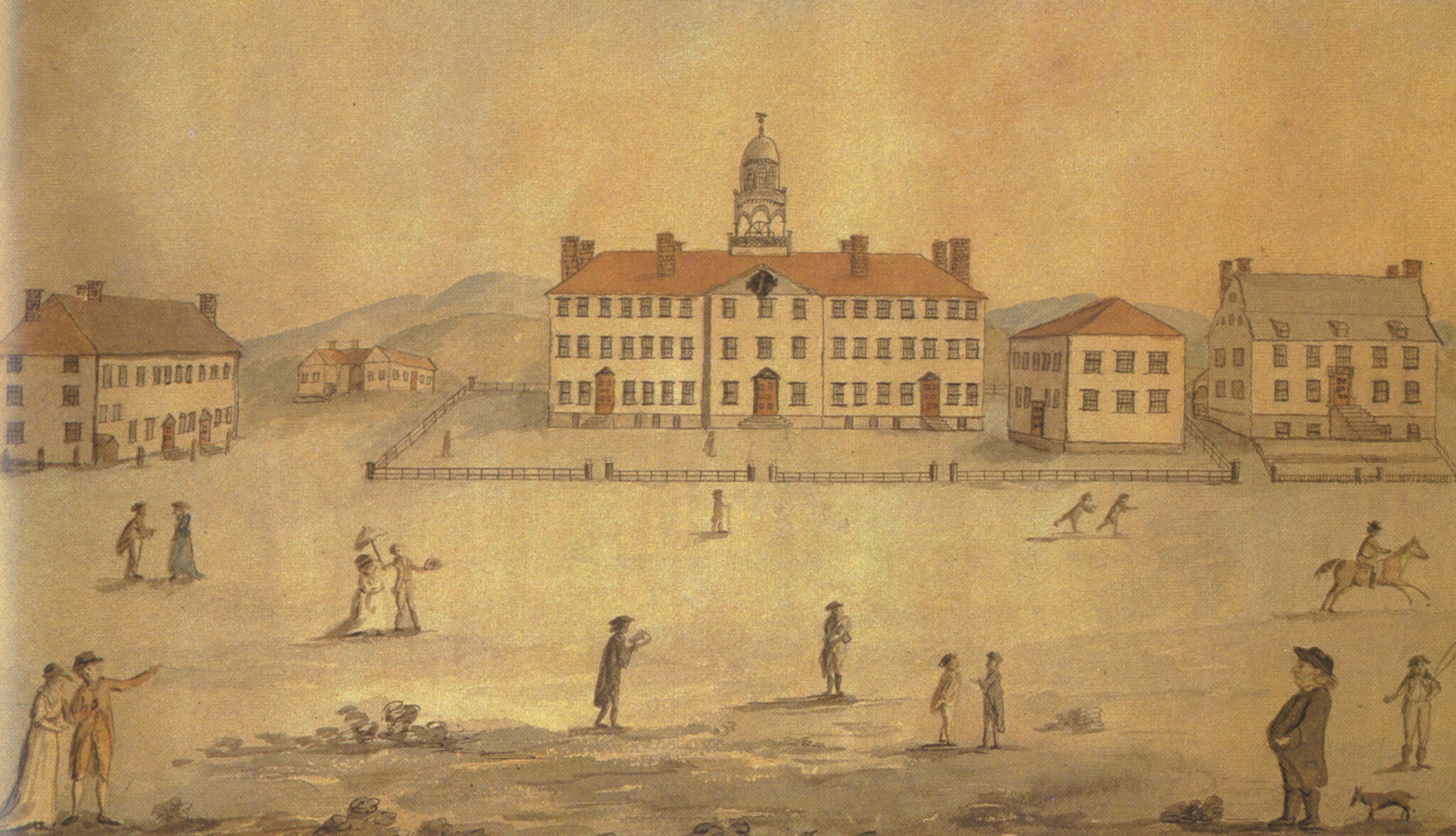

Governor Wentworth attended the first Dartmouth commencement in August 1771, and the following year presented an engraved monteith, known as “The Wentworth Bowl,” that is still used in the inauguration ceremonies of Dartmouth presidents.

Portrait of John Wentworth by John Singleton Copley

The Wentworth Bowl, photograph by Eli Burakian. Digital by Dartmouth Library

However, the competing demands of colonial governance would soon dominate Wentworth’s attention. Wheelock repeatedly wrote to the Governor seeking funding from the colonial assembly, but Wentworth struggled to manage the growing tensions among religious denominations, including those led by Great Awakening or “new light” clergy like Wheelock and Johnathan Edwards. He legally battled New York for control over what is now Vermont, while prosecuting those, including Wheelock, who stole the King’s timber. Most critically, between 1770 and 1775, Wentworth sought to mediate the escalating conflicts between the colonies and England that eventually led to the Revolutionary War and compelled his departure from New Hampshire8.

The extent of Gov. Wentworth’s enslavement of others is unknown. Most of his personal and financial records were lost when he and his family fled the mansion for the protection of the British fleet on Long Island. In December of 1776, he addressed a letter from there to the Marchioness of Rockingham. In gratitude for her hospitality toward, and safe-keeping of, his wife Frances and their newborn son, he sent a gift of two enslaved boys. Romulus and Remus, about 16 years of age, had been in his family since their childhood. Both played the French horn, and were described as being “faithful, honest and free from vice”.9 Their parents, Hagar and her unnamed husband, reportedly labored at Wentworth’s summer mansion in Wolfeboro, NH, as the war began.10

Wentworth eventually relocated to the British colony of Nova Scotia, where, from 1792 to 1808, he served as Lt. Governor. In February 1784, Wentworth wrote from the colony to a distant relative and friend, Paul Wentworth, that he was shipping nine men, six women, and four children, all enslaved, along with provisions for Paul Wentworth’s plantations in Surinam, Dutch Guiana.11 Each person was identified by name along with their skills, including carpentry, husbandry, boating, cooking, nursing. Also noted were the states of the women’s fertility. 12

Wentworth characterized the group as “either American born or well seasoned, and are perfectly stout, healthy, sober, orderly, industrious and obedient.”13 He asked that they all be “employed” together with Isaac as their overseer. Noting that he has had them baptized, Wentworth emphasized that he “would rather have liberated them than sent them to any estate that I am not sure of them treated with care and humanity.”14

"The Old Plantation," attributed to John Rose. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Notes

1. Great Britain. Sovereign. George III (1760-1820). “The governor's commission of vice-admiral. George the Third, by the grace of God, of Great-Britain, France and Ireland, King, Defender of the Faith, and so forth. To our well-beloved, John Wentworth, Esq; our captain-general, and governor, in chief, in and over our province of New-Hampshire, in America. Greeting...” Portsmouth, N.H.: s.n., 1767.

2. Van Deventer, David E. "Wentworth, Mark Hunking (1710-1785), merchant and politician." American National Biography. 2000; Accessed 7 Apr. 2023. https://www-anb-org.dartmouth.idm.oclc.org/view/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.001.0001/anb-9780198606697-e-0101133. Hugh Hall Wentworth (1740?-1777),a cousin of the governor,, was a shipping merchant and partner in Davenport & Wentworth, a British slave trading firm with agents in Antigua, Jamaica, New York, London, and other port cities. See Wentworth, Hugh Hall. Lesser Antilles Digital Collection. Hamilton College Beinecke Library, Clinton, NY, and Hugh Hall Wentworth Papers in the Larkins Papers, 1753-1814. MS010. Portsmouth, NH: Portsmouth Athenaeum. A Lt. Governor of Grenada,, he was an owner of the Mount Nesbitt estate in Grenada with 172 enslaved persons. (See ‘Hugh Hall Wentworth’ Legacies of British Slavery Database. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146631952. Accessed on October 19, 2022).

3. Wilderson, Paul W. Governor John Wentworth & the American Revolution: The English Connection. Hanover, N.H: University Press of New England, 1994: 85-86; and Samson Occom Journal, 1765 November 21. Ms. 765621.6. p. 22r. Occom Circle: Papers of Samson Occom, Dartmouth Libraries Digital Collections. https://doi.org/10.1349/ddlp.1132

4. To All People to Whom These Presents Shall Come, Greeting. Whereas It Has Pleased His Excellency, John Wentworth...for the Benefit and Instruction of the Indian youth...[Blank Deed of Gift]. New Hampshire?, n.d. Rauner Special Collections Library Broadside 000039. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College. Also see translated online version at: https://www.dartmouth.edu/library/rauner/dartmouth/dartmouth-college-charter.html

5. Chase, Frederick. 1891. A History of Dartmouth College and the Town of Hanover, New Hampshire, Vol. 1, p. 230.Edited by John K. Lord. Cambridge: John Wilson and Son University Press.

6. Wilderson, 1994, Chapter 7 “Man of the Interior: Developing the Frontier, 1767-1770,” pp. 115-134.

7. Roberts, Strother E. Colonial ecology, Atlantic economy: transforming nature in early New England. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019.

8. Wilderson, 1994. Also see Martin, James Kirby. “A Model for the Coming American Revolution: The Birth and Death of the Wentworth Oligarchy in New Hampshire, 1741-1776.” Journal of Social History 4, no. 1 (1970): 41–60. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3786345

9. Smith, Deborah J. “Lady Rockingham’s Black Horn Players.” Wentworth Woodhouse Preservation Trust Research Group, 2023. Accessed at: https://wentworthwoodhouse.org.uk/discovery/lady-rockinghams-black-horn-players/ (currently offline)

10. Parker, Benjamin Franklin. History of Wolfeborough (New Hampshire). Cambridge, MA: Press of Caustic & Claflin, 1901: p. 91

11. Chute, Sarah Elizabeth. “‘To ship her to the West Indies, and there dispose of her as a Slave’: Connections of Enslaved People to the Loyalist Maritimes and the West Indies,” Acadiensis: Journal of the History of the Atlantic Region, vol. 51, no. 2 (Autumn/automne 2022): 41-42. John Wentworth also kept two others, Matthew and Savannah, for his Nova Scotia household (p. 42).

12. Smith, Watson T. “The Slave in Canada.” Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society, 1896-1898, Vol. 10, pp. 51-52. Halifax, N. S.: Nova Scotia Printing Company, 1899, p. 51-52. Accessed July 23, 2023 online at: https://archives.novascotia.ca/pdf/africanns/F90N85-SlaveInCanada.pdf

13. Ibid, p. 51.

13. Ibid, p. 52.