John Thornton was a wealthy trader and philanthropist.

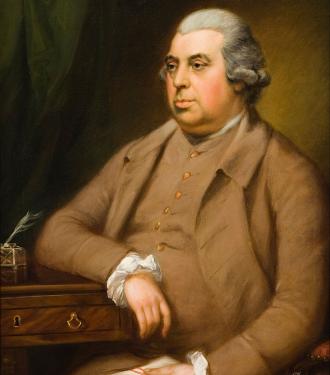

John Thornton (1720–1790) was an early, ardent, and loyal supporter of Eleazar Wheelock’s efforts to Christianize the Indigenous peoples of New England. A London merchant and Christian philanthropist, Thornton was respected for his generosity; dedicated to various charitable and Christian causes, he donated funds for building churches and schools, and for the printing and shipping of thousands of Bibles and hymnals around the world.1 As a trustee and treasurer of the English Trust that oversaw the Samson Occom-Nathaniel Whitaker tour of England and Scotland to raise funds for Moor’s Indian Charity School, Thornton was crucial to the success of the campaign (adding his own £100 to the total). Afterwards, and despite the Revolutionary War, Thornton helped sustain Wheelock and the fledgling Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, gifting the chaise that conveyed Wheelock’s wife and family to Hanover, and tapping personal funds to help pay for the construction of Wheelock’s mansion in 1771.2 He also extended an account against which Wheelock charged supplies and paid staff. Thornton Hall, on the Dartmouth campus, is named in his honor.

Thornton supported several Dartmouth-affiliated ministers but was especially dedicated to Occom’s ministry and family after Occom’s break from Wheelock over the latter’s abandonment of his Indian school.3 Thornton himself was wary of Wheelock’s motives and principles in founding the College, and he and the other British trustees insisted on strict accountability for the funds that were raised by Occom and Whitaker.4

Thornton also supported a number of other clergymen and Christian reformers, including the former slave trader John Newton, writer of the hymn “Amazing Grace," and the abolitionist William Wilberforce, who was a leader in the successful legislative campaign to ban Britain's slave trade. This is not to say that these men supported the full abolition of slavery. The earliest abolitionists (e. g. Wilberforce and Newton) sought to end the importation of additional slaves from Africa. Consequently, Britain's 1807 Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade did not abolish plantation slavery in its colonies. Newton, Wilberforce, and Thornton furthermore viewed the Society for Missions to Africa, which later became the Church Missionary Society and the British and Foreign Bible Society, as the means of salvation for Africans, enslaved or free—all three men promoted their exportation to Sierra Leone, rather than full citizenship in the Americas or the UK. It is likely no coincidence that Thornton’s son, Henry, was a founder and chairman of the Sierra Leone Company.

Thornton's evangelism was financed by a vast network of moneymaking enterprises that were entangled in British imperial objectives. The Thornton family had strong ties to banking—John, his father, father-in-law, two sons, and a nephew all served as directors of the Bank of England, established in 1694. The bank exclusively regulated bank notes, provided consumer banking services, and, significantly, used subscriber funds to help solidify naval prowess and sustain the British colonial empire around the globe. The family was also a partner in the Muscovy and Eastland Companies. Both firms held Crown-sanctioned monopolies on trade with Russia and Scandinavia that supplied timber, seafood, whale oil, and tallow to the the British Navy, and thereby to the nation's global explorations, trade, extractions, and colonization.

Portrait of John Thornton by Thomas Gainsborough

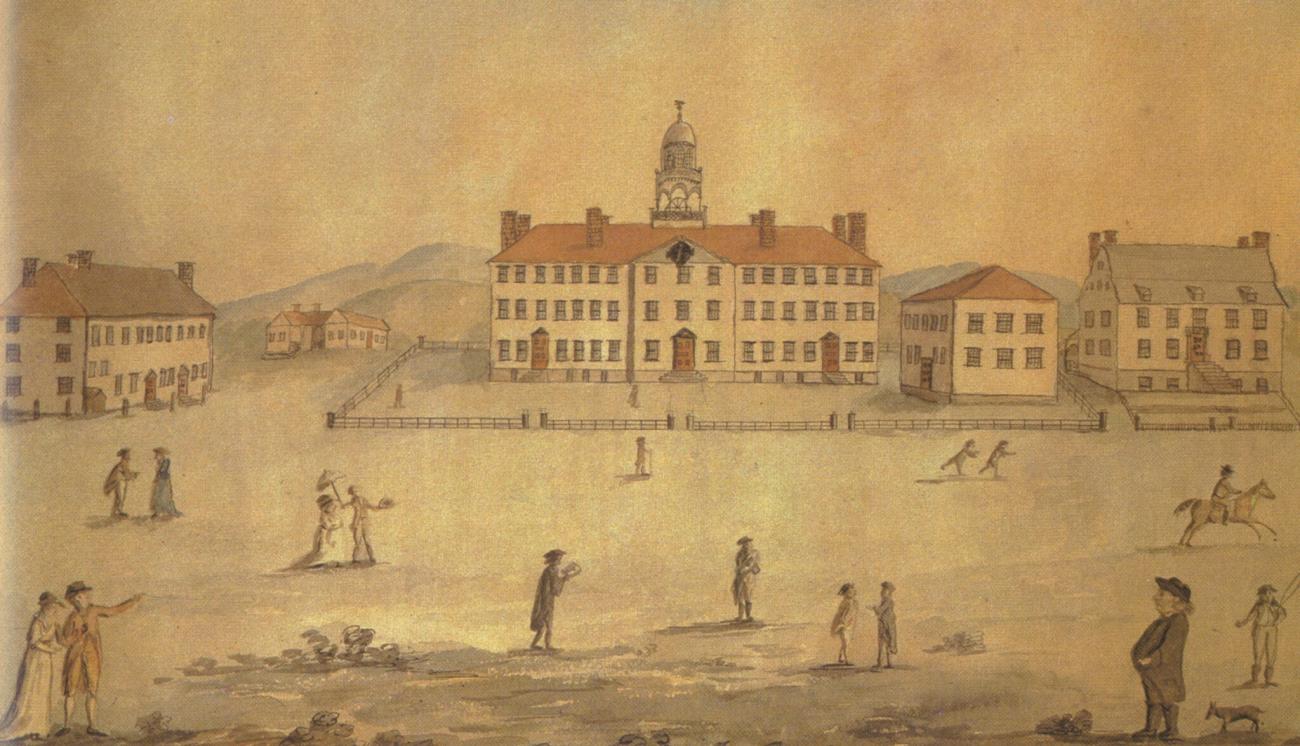

Hull Sugar House

Thornton’s personal firm—Pole, Thornton, Free, Down & Scott (1773-1825)—was the London agent for provincial banks throughout the British Isles, and financed a variety of economic activities related to the transatlantic slave trade. Another firm, Thornton & Watson, operated a soap-making factory and a sugar refinery in Hull. Thornton also developed a diverse portfolio of leased houses, farmlands, warehouses, and wharves, and was engaged in the chandlery and leather businesses. At his death in 1790, he had allegedly amassed the second largest fortune in all of Europe.

Notes

1. Milton M Klein, An ‘Amazing Grace’: John Thornton and the Clapham Sect (New Orleans: University Press of the South, 2004); Edwin Welch, “Thornton, John (1720–1790), merchant and philanthropist,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Online ed. 2004, 10.1093/ref:odnb/27358, accessed 7 February 2021; Mary Seeley, The Later Evangelical Fathers: John Thornton, John Newton, William Cowper, Thomas Scott, Richard Cecil, William Wilberforce, Charles Simeon, Henry Martyn, Josiah Pratt (London: Seeley, Jackson, & Halliday, 1879).

2. Frederick Chase, A History of Dartmouth College and the Town of Hanover, New Hampshire, Volume 1, (Cambridge: John Wilson and Son, 1891).

3. See Samson Occom's letters to John Thornton; and John Thornton, letter to Eleazer Wheelock. Thornton also sustained Samuel Kirkland; see their correspondence in the Samuel Kirkland Collection at Hamilton College. In addition to his financial support, Thornton sought to mediate both men’s conflicts with Eleazar Wheelock.

4. See Chase, A History of Dartmouth College, especially Chapter V, which contains copies of the letters from the Trust.