Would you rather overhear your doctor tell your nurse “The brain aneurysm in room 338 needs your attention” or “Mike in room 338 is feeling unnerved and could really use some support?”

Your response to this question reflects what is now recognized as the “medical gaze.” The “medical gaze” reflects the relationship between doctor and patient, wherein a suffering patient relies on an authoritative and knowledgeable caretaker. And yet this idea that a doctor sees a patient as a collection of symptoms or pathologies – perhaps instead of seeing them as a whole person – represents historical and social change. French philosopher Michel Foucault developed the phrase in 1963 to portray the 19th century medical profession and its shifts from earlier orientations of medical practice. Foucault claims that the concept of the medical gaze can be summed up in the shift from physicians asking patients “What is ailing you?” to asking, instead, “Where does it hurt?” The first question is meant to encompass how a disease, pain, or symptoms affect the entirety of the patient and his life; the second question focuses on parts and symptoms, not the whole person.

While Foucault has made a powerful point, in this exhibit we explore how medical gaze is dynamic, reflective of the partnership between physician and patient, and not always solely focused on parts or cures.

In earlier periods of medical history, especially Medieval and Renaissance sources we explore in this exhibit, the medical profession’s understanding of the patient was portrayed in more humanistic terms. Images and texts often focused on the connection between mind and body in relation to a person’s life experiences – and even to things like religion and astrology, in which understandings of health and illness were imbedded. In many of these early sources, it is as if the doctor gains understanding of the patient through his overall life story or place in society. This may be attributed to not only societal views of medicine, but also a lack of modern medical knowledge, technology, and techniques at that time.

These images reflecting earlier versions of the medical gaze contrast with later depictions of patients as a collection of parts, or a disease category rather than a person. Foucault explains, “Facilitated by the medical technologies that frame and focus the physicians’ optical grasp of the patient, the medical gaze abstracts the suffering person from her sociological context and reframes her as a ‘case’ or a ‘condition’” (2003: 23) The doctor, in this case, strives for disease treatment, but not necessarily patient care.

The texts in this exhibit highlight the cycles and trends of the medical gaze throughout history. We begin in 1500, a time when medicine was represented as more humanistic, capturing the value of life experiences and the relationship between, mind and body, soul and society. We then take you on a journey through time, exploring the medical world’s transition into specializations, which serve to create further distance within interpersonal doctor-patient relationships by concentrating on parts in need of attention rather than a whole person in need of empathic treatment. Finally, we will explore the revolution of the medical gaze, revisiting the ways that 15th and 16th century values of humanistic medicine have resurfaced, while also taking advantage of modern advancements in medical knowledge and science.

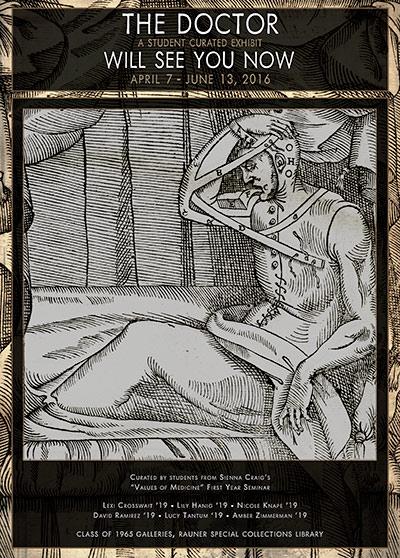

- A Caregiver’s Guide (Joannes de Ketham, Fasciculus Medicine. Venice: Joannem et Gregoriu de Gregoriis Fratres, 1500.) Incunabula 74

- 1500: Ketham’s Fasciculus Medicine, the first published medical textbook with anatomical illustrations, teaches doctors how to administer care to best help the afflicted person. A picture within the text portrays doctors tending closely and carefully to a patient. Since the illustration above depicts the full body instead of individual afflicted body parts, medicine at this time focused on how these afflicted parts affect the person as a whole. Although doctors must examine afflictions to individual regions of the body, they most importantly must investigate how all afflictions compose the patient’s overall condition.

- Peeling Away the Layers (Juan de Valverde. Anatomia del Corpo Humano. Rome: A. Salamanca et A. Lafrerj, 1560.) Rare Book QM21 .V35

- 1560: Notice how this illustration now focuses on the layers of the body. The medical gaze narrows: by studying musculature and the nervous system, doctors form a comprehensive view of the individual’s condition and whole-body health. We begin to see a division of the body, while maintaining a humanistic, or personal, view of medicine.

- Instruction Manual (Jean Cruveilhier. Anatomia Pathologique du Corps Humain. Paris: J. B. Bailliere, 1829-42.) Rare Book RB33 .C96 (2 volumes)

- 1842: 300 years later, medical textbook artists stray from sketching the natural curves of the body covered in muscles or skin. Instead, they create colorful illustrations of diseased ovaries and pathologic hearts. The illustrations not only suggest the beginning of specialized fields in medicine, but also portray “normal” versus “abnormal” body structures. Doctors learn not so much individualized patient care, but rather comparative views of patient symptoms reflective of determined “standards.”

- The Manual Fails (Ann Kalmbach. My Nine Migraine Cures. Rochester: Visual Studies Workshop, 1987.) Sherman Special N7433.4.K35 A4 1987 (not available at Rauner)

- 1987: “Aspirin - NOT BETTER YET.” My Nine Migraine Cures expresses the frustrations that patients when they suffer from symptoms that doctors cannot treat. With this more modern turn in the medical gaze, doctors pay less attention to patient narratives and fail to listen, which can undermine finding the most effective treatment. They resort to prescriptions that “normally” work, such as Aspirin for headaches. In this case, as anthropologist Susan Greenhalgh explains, there exists a “disjunction between the physician’s narrow view of his task as finding and fixing disease, and the patient’s larger view of her illness as part of a life that needs to be put in order” (2001). When “normal” treatments do not work, doctors cannot provide further care if they do not understand the patient’s narrative.

- Patient Speaks (Martha Hall. Legacy. Orr’s Island: M. Hall, 2001.) Presses H166hale

- 2001: The book may be small, but the message is bold: “Your books will be your legacy.” A week before Dartmouth Tuck Business School graduation, Martha Hall was diagnosed with breast cancer. Working for better cancer patient care, she founded the Cancer Community Center in South Portland, Maine. She represents her frustrations toward the medical community in her artist books, revealing her doctors’ insufficient support. Hall takes healing into her own hands by standing up for herself, demanding better care. If she does not speak up for herself, no one will. ATTENTION, Hall screams. There is a need to reform the medical gaze.

- Physician Answers (Martha Hall. Voices: Five Doctors Speak. Orr’s Island: M. Hall, 2001.) Sherman Special N7433.4.H355 V65 1998 (not available at Rauner)

- 2001: Good news! The language implemented by this particular doctor on this page of Martha Hall’s Voices inspires a transition back towards patient-centered care in the medical profession. The rhetoric a doctor uses in a conversation with a patient easily dictates the direction of the discussion and the patient’s comfort with sharing more information about himself. Although this particular page shines hope on the situation of the current medical gaze, many of the other pages reflect lack of personalization by four other doctors. The contrast works to represent the reality of the variation in the medical gaze.