Edward S. Curtis. The North American Indian: being a series of volumes picturing and describing the Indians of the United States and Alaska. Seattle, Wash.: E. S. Curtis; Cambridge, USA, The University Press, 1907-1930. (Rare E77.C982 1907 v.6)

Edward Curtis’ photographs were initially celebrated for their ability to capture Indigenous life “before the race vanished forever.” However, it was later discovered that Curtis manufactured his images, posing individuals how he saw fit and asking them to wear articles of clothing that were not customary to their communities. This emphasizes the issue with settler conceptions of Native cultures and depictions.

In one of his most infamous alterations, Curtis removed a clock from a staged portrait. The original In Piegan Lodge depicts two Blackfeet individuals, Little Plume and his son Yellow Kidney, sitting with a pipe, tobacco, the clock, and more. It is unknown who selected these items for the picture. Later adaptations of the image feature a basket where the clock once was; to create this idealized, romanticized, and antiquated version of Indigenous peoples that Curtis was notorious for, he manipulated his photographic plate to remove the clock, falsifying every subsequent print that was produced. Rauner has the edited image.

Thomas L. McKenney, et al. History of the Indian tribes of North America: with biographical sketches and anecdotes of the principal chiefs. Philadelphia: J. T. Bowen, 1848. (Rare E77.M1305 v.1)

The drawings in this book were completed by Charles Bird King and commissioned by Thomas McKenney. McKenney oversaw the Bureau of Indian Affairs (or the “Indian Office” as he called it) from 1824 to 1830. As part of his work, McKenney requested meetings with tribal leaders from the eastern United States so that portraits could be drawn and entered into archives. At this time, the BIA fell under the jurisdiction of the War Department, which is indicative of how the United States viewed Native relations.

This illustration of Sequoyah, a prominent Cherokee leader and visionary, was completed in 1828 during Sequoyah’s trip to Washington, D.C. He was visiting the U.S. capital to advocate for his community during a highly contentious period for eastern tribes. Sequoyah, also known as George Guess, is best known for his creation of the Cherokee Syllabary, which would later be used to print the Cherokee Phoenix –the first newspaper published by Native Americans in the United States. Members of the community used these two facets to articulate their positions for or against removal prior to the Trail of Tears. Both the Syllabary and Phoenix exist today.

Cherokee Nation, Oklahoma. Constitution and laws of the Cherokee nation: Published by authority of the National council. St. Louis: R. & T. A. Ennis, printers, 1875. (Rare E99.C5 C47 1875)

This iteration was created following the forced removal and subsequent division of the Cherokees. Both the Eastern and Western Cherokees signed the document, with Sequoyah representing the West as George Guess. The original Cherokee constitution was ratified in 1827, predating the Indian Removal Act that would later threaten the tribe’s integrity. The Cherokee Constitution was modeled on that of the United States Constitution, exemplifying the community’s transition into modernity while also asserting their self-governance. However, such advancements were still not viewed as significant enough to combat forced removal from their ancestral lands. Despite the atrocities committed against the Cherokees, the production of this document continues to signify their status as a unified, sovereign nation.

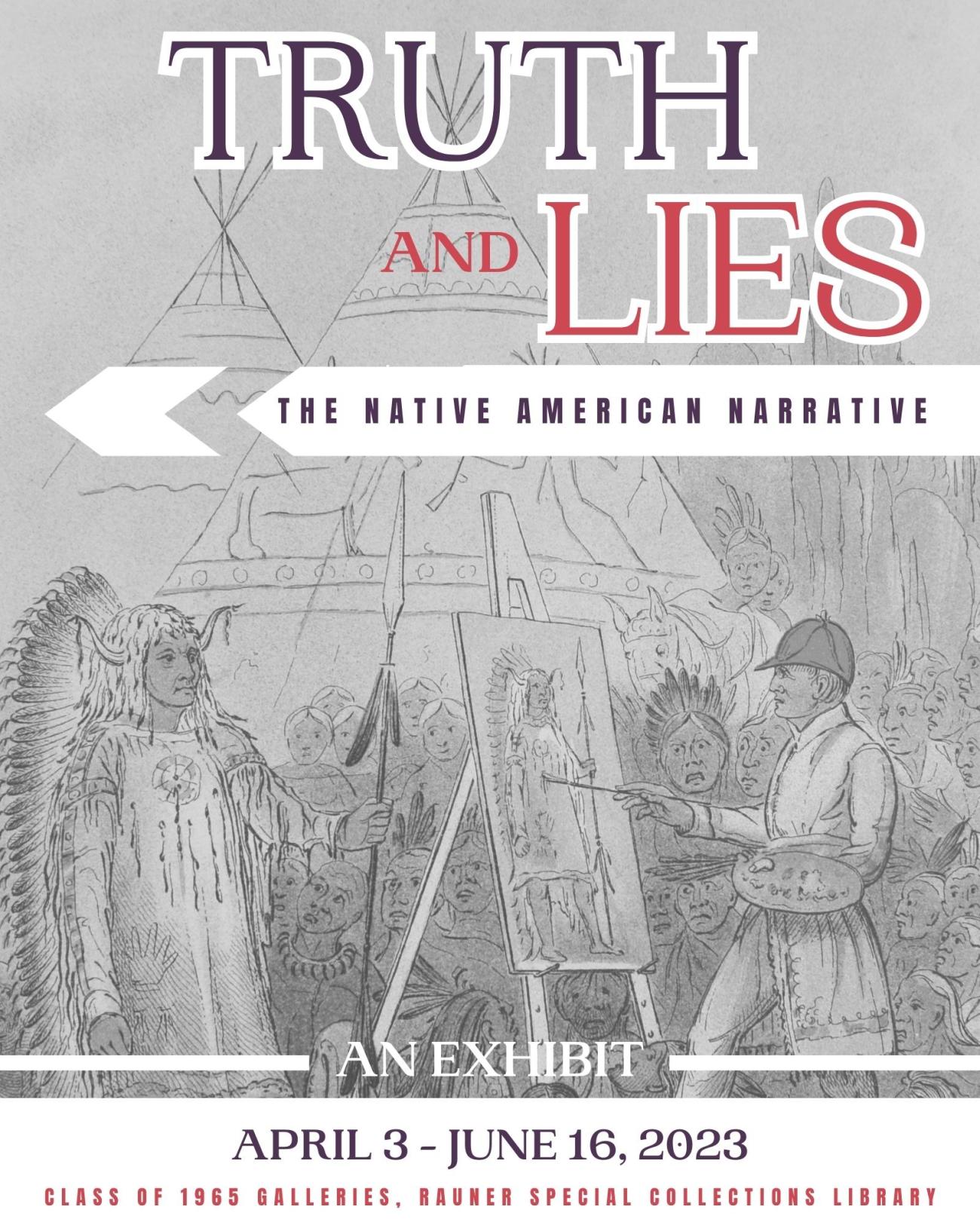

George Catlin. The manners, customs, and condition of the North American Indians. London: George Catlin, 1841. (Rare E77.C4 v.1)

From 1832 to 1839, George Catlin traveled west of the Mississippi River; for European populations that had settled on the east coast of the U.S., there was minimal information available to them about what existed “on the frontier.” Catlin’s expedition provided a new and varied perspective of this region, as he met with numerous Native communities to conduct landscape and portrait drawings. Like most works from this period, Catlin’s art embedded the themes of imperialist nostalgia and colonization with an objective similar to Curtis’ photographs.

But Catlin received much disapproval from his peers, as he was outspoken about the negative impacts colonization was having on tribal communities. Nonetheless, Catlin still felt entitled to invade Native territories to complete his project, which precipitated conflict amongst some groups. In the present, it is difficult to reconcile his ideologies and his actions, especially as it is unknown if Catlin sought input from different tribal leaders about their portrayal in the images.

Theodore Frelinghuysen. Speech of Mr. Frelinghuysen, of New Jersey, delivered in the Senate of the United States… on the bill for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for their removal west of the Mississippi. Washington: Office of the National Journal, 1830. (Jeremiah Smith Pamphlet Collection, v. 24:15)

Frelinghuysen represented New Jersey in the United States Senate from 1829 to 1835. However, Frelinghuysen was not highly regarded by his peers, as he was in staunch opposition to the Indian Removal Act touted by President Andrew Jackson. Frelinghuysen delivered a six-hour long speech against the Act in April 1830, highlighting the consequences it would have for Indigenous peoples. The Act was eventually signed into law on May 28th, 1830.